In an October interview with

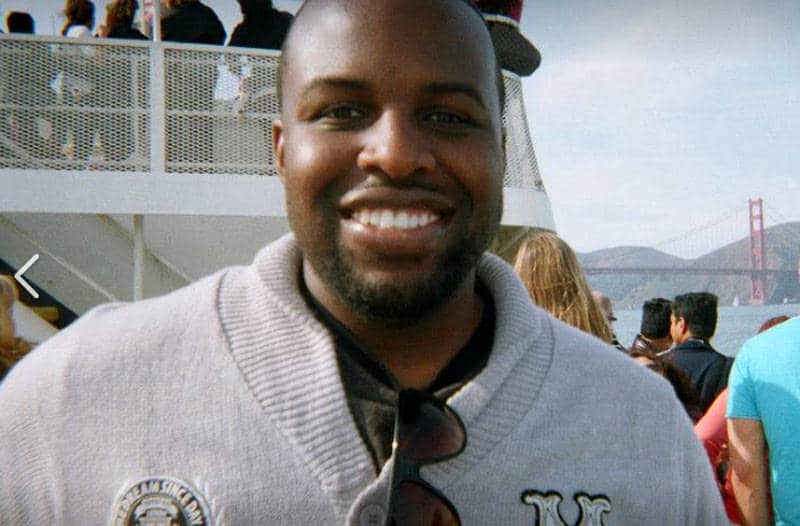

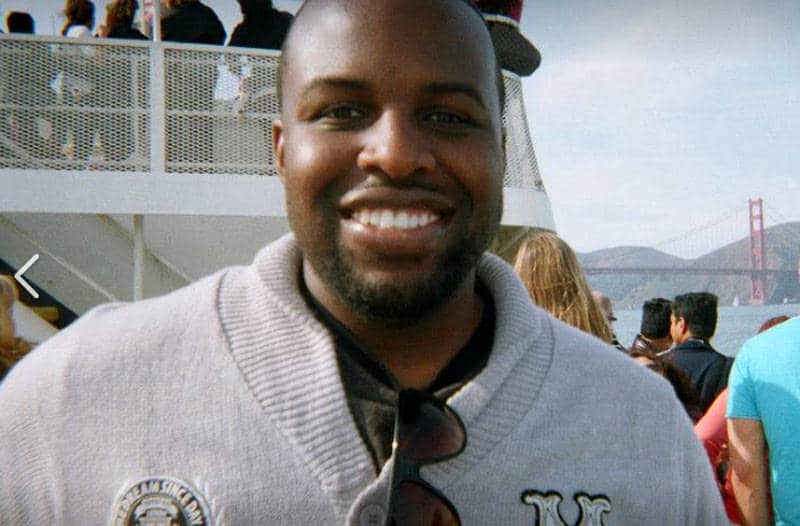

Upfront News on Berkley’s KPFA Radio, Facebook executive Ebele Okobi describes her brother Chinedu as a kind and gentle man who was nonjudgmental and curious, and who made friends wherever he journeyed.

This is not, of course, the Chinedu Okobi described by The San Mateo Sherrif’s Office after sheriff’s deputies tased him to death while he was in the throes of a mental health crisis.

The demonization of Chinedu Okobi—who was described as tall, big and aggressive, words often used to turn Black victims of police violence into perpetrators and justify their deaths—is a familiar script that leads to no accountability for officers who use excessive force.

It is a script that perpetually fails to acknowledge Black people’s full humanity.

Details are still sketchy about what happened between Chinedu Okobi—the Nigerian American father, poet and Morehouse grad—and sheriff deputies on the afternoon of October 3, 2018. Okobi (who was unarmed) was said to be running in and out of traffic on a street called El Camino Real in Millbrae when he was approached by one deputy, who claims the victim “immediately assaulted” him.

According to reports, two of the five deputies responding to the incident tased the victim a total of four times to “get him under control.” That tasing—which Okobi’s family believes was excessive—lead to the victim going into cardiac arrest. Okobi was transported to Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, where he was pronounced dead.

In that same interview with

Upfront, Ebele Okobi recalls that her brother had recently experienced a difficult breakup and may have been off of his mental health medication when he was killed. And while all the details of what happened may not be clear, one thing is: Chinedu Okobi needed help from the deputies that harmed him, which is too often the case when police officers interact with individuals experiencing mental health crises, and especially when those people are Black.

According to the

Washington Post, throughout 2015 and 2016, almost 500 people killed by police lived with mental illness. This means that 1 in 4 people killed by police during those years were mentally ill. In 2017 alone, almost 300 people with mental illness were killed by police. Chinedu Okobi’s death highlights a stark and disturbing reality regarding the fate of far too many people who are Black and mentally ill. Black people such as

Jontell Reedom,

Charleena Lyles (who was killed by police while pregnant and while her children were inside their home), and

Shukri Said, who was killed by police near Atlanta, Georgia.

Often, as with the cases of Jontell Reedom and Shukri Said, family members call emergency lines for help, hoping to have first responders de-escalate incidents involving their loved ones, and possibly get them on a fast track towards treatment. However, police officers seldom possess the training necessary to support and care for those experiencing mental health crises. John Snook, who is the executive director of Treatment Advocacy Group and the co-author of the study “Overlooked in the Undercounted: The Role of Mental Health Illness in Fatal Law Enforcement Encounters,”

writes that by dismantling mental health treatment systems “…we have turned mental health crisis from a medical issue into a police matter.”

Mental illness has not only become a police matter in the United States, but it has become a broader issue within the entire criminal justice system. At least

10% of police calls involve interactions with the mentally ill. In almost every state within this nation,

prisons hold more people living with mental illness than associated state hospitals. Jails in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago are the largest institutions

providing psychiatric care in America. This trend means that, as a society, we are criminalizing the mentally ill, and it also means that those living with mental illness are very likely not receiving the treatment that they need and deserve.

Psychologist and professor Dr. LaWanda Hill has noted the effects of both of the overcriminalization of the mentally ill and issues with diagnosis and treatment in prisons—especially when those incarcerated are people of color. She shared with Essence.com that while completing clinical rotations at a federal detention center in Lexington, Kentucky, she noticed that there were more people of color who were incarcerated than there were people of color living as free citizens in that town.

“Moreover, when I began my clinical work with people of color, I quickly learned that many people of color suffered from mental illness and were either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed… I also learned quickly that many of their substance use and criminal activity in some capacity were either related to undiagnosed mental illness or unaddressed maladaptive forms of coping.” Hill writes.

Although prisons have become the nation’s largest mental health facilities, prisoners often still do not receive proper mental health care. Like police officers, prison employees (outside of medical professionals, possibly), have little to no training on how to care for inmates who are mentally ill. Often, incarcerated people end up staying in prison longer, are victimized while in prison, and see their mental health issues

worsen. And others, who experience severe mental health crises while incarcerated, end up dead.

Natasha McKenna comes to mind: a Black woman who was bipolar schizophrenic and was tased to death—much like Chinedu Okobi— while experiencing a psychotic break in prison. McKenna, just like Okobi, needed medical intervention, not a violent take-down that would eventually kill her.

There are more questions than answers when considering how all of us can help people living with mental illness escape violence connected to police interactions and incarceration.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) has established a program called

The Stepping Up Initiative that hopes to divert the mentally ill from prisons and into treatment, instead. NAMI also partners with city officials to create crisis intervention teams that go out with local law enforcement to provide support for individuals who may be experiencing a mental health crisis.

As far as what we can do to honor the memory of Chinedu Okobi, Color of Change has established a petition demanding that San Mateo District Attorney Steve Wagstaffe charge and prosecute all officers involved in Chinedu’s murder. Sign it

here.