ATLANTIC CITY, N.J. – “I lost all my rights. I felt like I failed my family,” Marcella Soto shares with ESSENCE. She was receiving welfare benefits and was in an on-again-off-again relationship with her husband. In 2018, during one of those off periods, she was charged with welfare fraud, as the courts presumed her husband was still residing with her, violating the conditions of government assistance.

Instead of standing trial and potentially facing a maximum 20-year prison sentence, she took a plea deal and accepted a five-year probation.

Though Soto was not incarcerated in a cell, probation simply widened the geography of her imprisonment– she couldn’t leave the state throughout her probation sentence without jumping over restrictive hurdles.

“I was restricted [from doing] anything,” she says. “I couldn’t see the birth of my grandchild. I couldn’t be there for my daughter when she needed me. Even to go to her baby shower was a process. I had to pay legal feels to even get permission to see her.”

Missing her first grandchild’s birth was especially heart-wrenching. Soto knew the due day, but as it’s commonly known, a baby can be born at any time. “We [didn’t] have an exact date, and [the officer] said that because I didn’t give her a two-week notice, I could not be there. I felt like I failed not just my daughter, I failed my first grandchild.”

In addition to missing family events, Soto lost out on a job opportunity– which are hard enough to find given the ongoing discrimination against workers who have been justice-involved. The job required out-of-state travel, which she couldn’t do unrestricted.

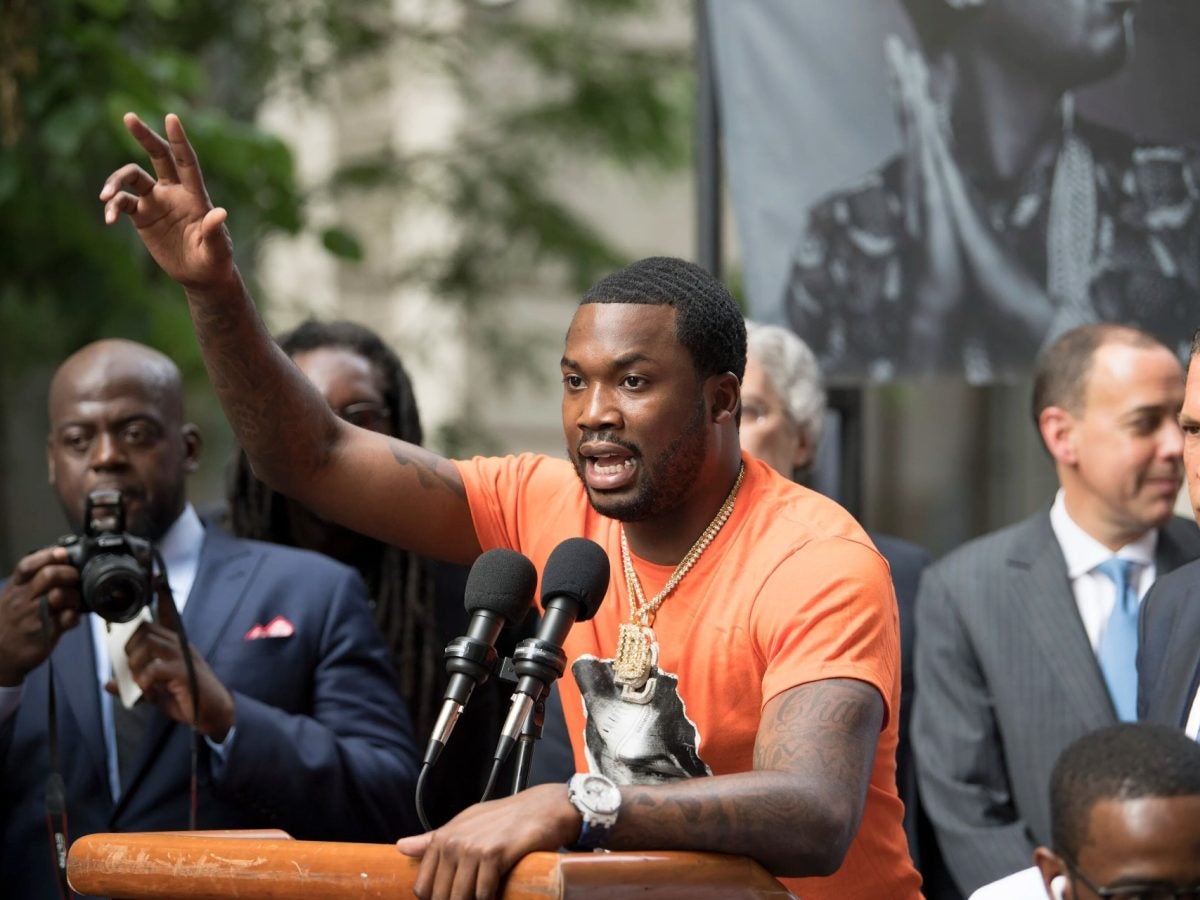

Soto began looking for an out when she stumbled upon rapper Meek Mill’s story and the REFORM Alliance, a non-profit he founded with Mark Rubin and other advocates to reform parole and probation laws nationwide.

She discovered that REFORM successfully lobbied to shorten California’s probation terms, with certain exceptions, to a two-year maximum under state assembly bill AB-1950, which became law in September 2020.

Marcella has since left the state and is now enjoying life as a grandmother with her family in Oklahoma.

While Soto eventually found a way out, millions of Americans remain under supervision. Though they’re not locked up, they’re locked out of key aspects of society. In fact, more people are under the supervision system than those who are incarcerated, with an estimated 3,890,400 adults on probation or parole in 2020, compared to about 2 million in prison and jail.

Social impact influencer Wallo is among them. At a star-studded fundraising gala held by REFORM Alliance on Sept. 30– hosted by Meek Mill, Jay-Z, and Michael Rubin– the criminal justice advocate silenced the audience with his testimony and took the A-list crowd to task.

Wallo was arrested at 11 years old for armed robbery, and he has yet to be out of state supervision since. “I’ve been out of prison for six years. I get off parole October 29, 2048,” he tells the audience.

Being on parole leaves people in a world of precarity. “Just to be here, I had to get permission,” he tells Kevin Hart, who hosted a fireside chat with Wallo during the REFORM fundraiser, which raised $24 million for the organization’s advocacy. “I had to get travel papers. I could go back to jail tomorrow.”

Wallo pleaded with the audience to support those impacted by the system, “In order for this world to work we gotta come together. We gotta help the people that just ain’t got it, and because of their geographical location and color of their skin they’re not gonna get a fair shot,” he urges.

“Some people was born into some serious situations. I’m challenging everyone in this room, help when nobody sees you helping,” he continued.

REFORM CEO Robert Rooks echoed those sentiments, calling criminal justice “one of the defining social and economic issues of our time.”

“We cannot advance racial justice without addressing the vicious racial inequities plaguing our justice system,” he said in a statement to ESSENCE, also noting the gender implications. “When we remove barriers and build opportunities for Black women to belong and to succeed, it makes our society stronger.”

Without those opportunities, they also face the insecurity and life-altering outcomes of imprisonment.

“Y’all see me now, ain’t no telling when y’all won’t see me,” Wallo shared before pausing to hold back tears during his fireside chat, implying that he can be locked up for minor infractions of his parole.

Some of these infractions may be what are called “technical violations” that can send people back to prison without them having to commit any new offenses, like failing to report to a visit with a probation or parole officer.

James Severe was on parole while pursuing a bachelor’s degree in New York. While just one semester away from graduation, he was pulled over and learned that he had a five-month old warrant. The warrant was issued after he had unsuccessfully tried to contact his parole officer, but the PO had actually retired and was unreachable.

Severe received a technical violation and was reincarcerated. During that time, he lost his job, housing, and all of the credits he earned that semester ahead of graduation.

Before he was sent back to prison, he was playing football in college and preparing for his career. “I was doing everything that I set for myself, and the technical violation stripped all of that.”

Now off parole, he has had to find alternatives to pursue his career, which was to be a sports agent.

“I walk in here today on unemployment. I can’t pass a background check,” he shares ahead of the REFORM dinner. But he’s still studying to be an agent.

Severe returned to school through a program offered by Roc Nation and Long Island University. “I’m 30, I’m back in school. I go to the Roc Nation school [as] a sports management major.”

“Oftentimes what’s available to us [who are] formerly incarcerated are trades, you know, washing dishes, putting our heads down, just making money. I feel like I have a voice for just a different direction, [and to show] we can be normal.”

When asked about what advice he would offer to people under America’s repressive supervision system, he says it was important to keep going. “It’s hard. You’re not going to know what you’re going to find at the end of the rainbow, you just got to believe in yourself.”