Many of us may be familiar with the story of the Underground Railroad as a northern route that enslaved Africans used to escape and find freedom. A largely untold story, however, is about the journey to freedom for many enslaved people from Texas to Mexico and Silvia Hector Webber’s important role in helping them get there.

Now, the exhibit “Freedom Papers: Evidence of Emancipation” at the University Of Texas- Austin will change that as Webber’s story is at the center of it.

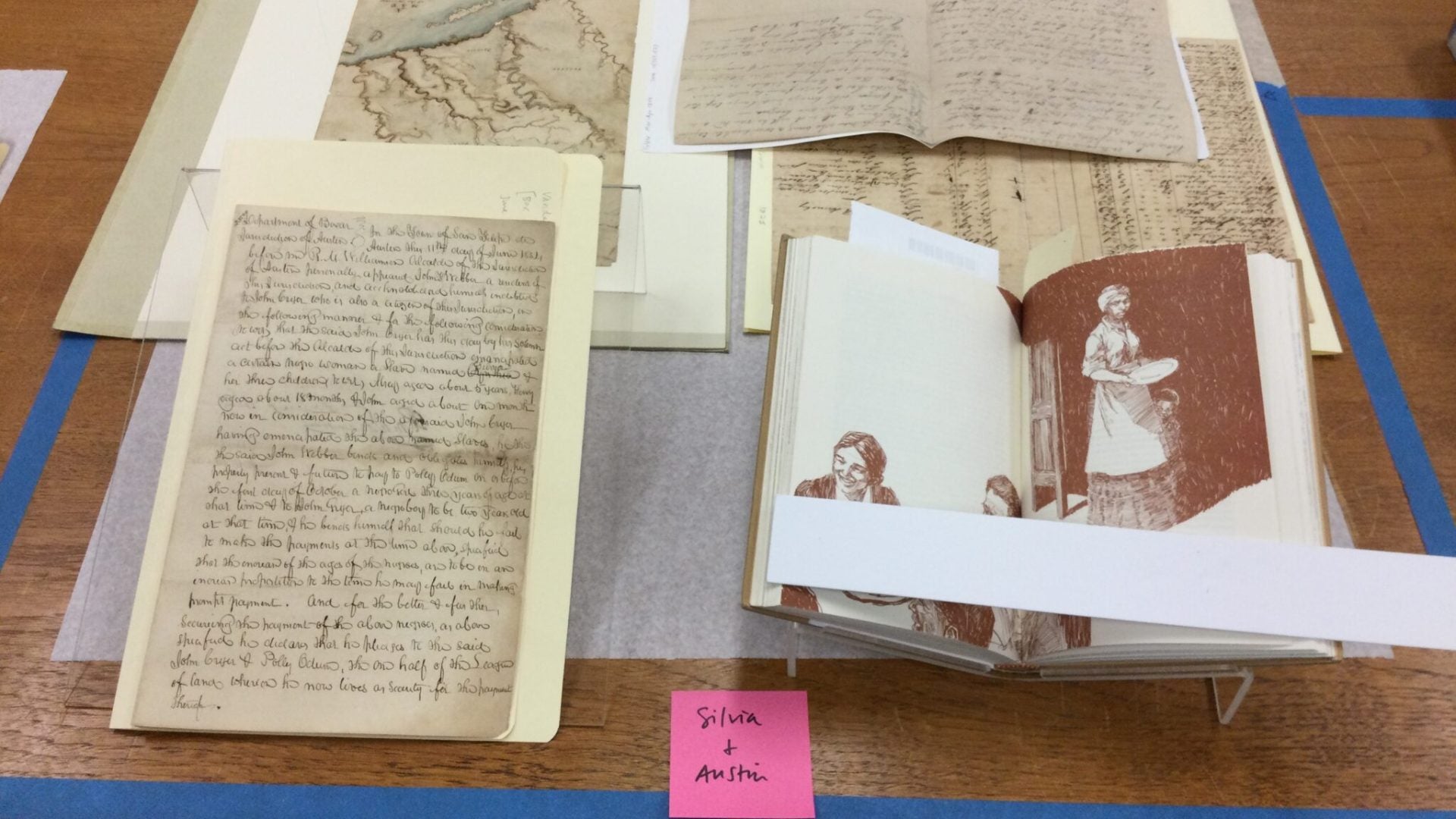

The exhibit at UT-Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History showcases a variety of documents to convey what it took for enslaved people, primarily women and children, to be freed before the Emancipation Proclamation.

One of those documents is Webber’s emancipation papers, which show that her family gave up over 800 acres of land in exchange for freedom for her and her children.

According to The Briscoe Center, once Webber gained her freedom, she helped others gain freedom via travel to Mexico, and her home became a stop on the Underground Railroad. The Webber land, located east of Austin, is now present-day Webberville, Texas. Mexico had fully outlawed slavery in 1837, well before the United States did so with the 13th Amendment in 1865.

“This provides us with real primary source evidence of the experience that people went through trying to gain their freedom and trying to exist in a world where they were born without human rights,” Sarah Sonner, the center’s associate director for curation told NBC News affiliate, KXAN News in Austin. “It lets us form a personal connection to lives that happened before the Civil War.”

“We know what their names were. We know where they lived, where they grew up, where they were born,” Sonner added.

Initially, Webber came to Texas during the Austin expedition with her owner, John Cryer. She later met her future husband, John Webber, in Central Texas. In 1832, he purchased a large parcel of land east of Austin. This was the land he would eventually use to obtain Sylvia’s freedom.

Eventually, the Webber family headed to South Texas and settled in the Rio Grande Valley, where their 8,000-acre ranch became an outpost of the Underground Railroad, where she and her husband helped enslaved people find freedom by crossing the border into Mexico.

“She was known as a generous hostess and a real comfort for people who sought her help,” said Sonner. “So Sylvia’s house served as a welcoming refuge for people seeking their freedom.”

Sonner said the exhibit’s goal was to convey the fragility of freedom, as several documents depict difficulty maintaining status when traveling from state to state.

“This is a shared history, especially in Sylvia’s case. This is land that we can identify,” she said, “and I think that it, moreover, provides us with personal connections and understanding. These primary sources illuminate so much more than a history textbook can.”

Curators hope that the exhibit will provide a better understanding of Webber and others like Texas’s and Mexico’s unique role in emancipation long before president Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

The “Freedom Papers: Evidence of Emancipation” exhibit will be open until June 28.