The South Carolina House voted Wednesday, May 5, to add a firing squad to the state’s execution methods amid a lack of lethal-injection drugs—a measure meant to jump-start executions in a state that once had one of the busiest death chambers in the nation.

The Senate already had approved the bill in March, by a vote 32-11. It will now require condemned inmates to choose either being shot or electrocuted if lethal injection drugs aren’t available. The state is one of only nine to still use the electric chair and will become only the fourth to allow a firing squad. The House, which only made minor technical changes to that version, will send this off to Republican Gov. Henry McMaster, who has said he will sign it.

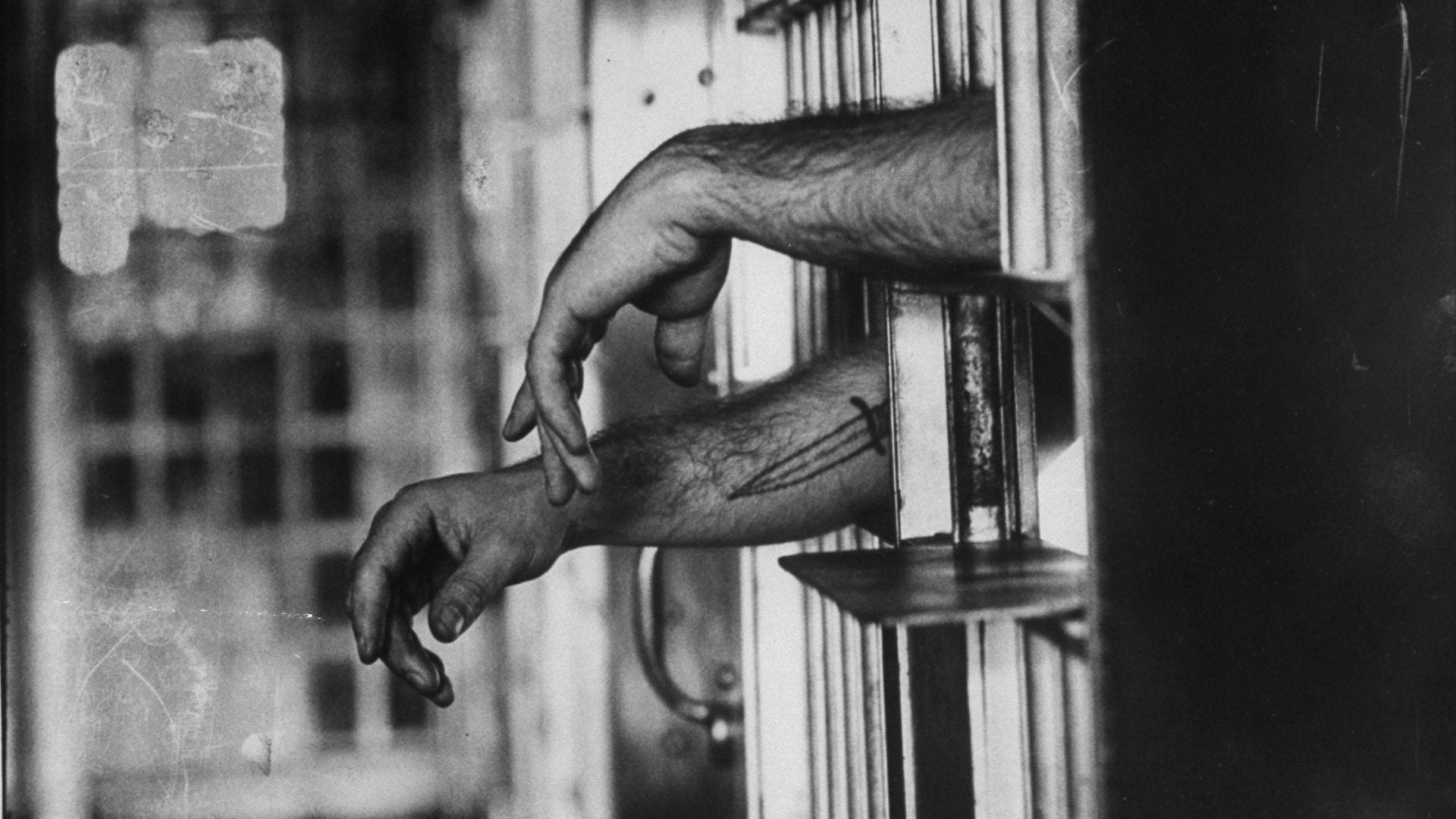

While three of South Carolina’s 37 death row inmates are out of appeals, there are several prisoners in line to be executed. “Three living, breathing human beings with a heartbeat that this bill is aimed at killing,” said Democratic Rep. Justin Bamberg. “If you push the green button at the end of the day and vote to pass this bill out of this body, you may as well be throwing the switch yourself.”

The Palmetto State first began using the electric chair in the early 1900s after taking over the death penalty from individual counties, which usually hanged prisoners. Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Utah are the other three states that allow a firing squad, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. Three inmates, all in Utah, have been killed by firing squad since the U.S. reinstated the death penalty in 1977. Nineteen inmates have died in the electric chair this century alone.

South Carolina has gone without a method to put anyone to death because its supply of lethal-injection drugs expired, and it has not been able to buy any more. Today, those on death row can choose between the electric chair and lethal injection. The bill does retain lethal injection as the primary method of execution if the state has the drugs, but requires prison officials to use the electric chair or firing squad if it doesn’t.

“Those families of victims to these capital crimes are unable to get any closure because we are caught in this limbo stage where every potential appeal has been exhausted and the legally imposed sentences cannot be carried out,” said Republican Rep. Weston Newton. Adding to the lack of drugs are decisions by prosecutors who seek guilty pleas with guaranteed life sentences over death penalty trials, which led to the state’s death row population cut nearly in half—from 60 to 37 inmates—since Jeffrey Brian Motts was the last execution carried out in 2011.

Before that, South Carolina averaged just under two executions a year from 2000 to 2010.

Democrats in the House offered several amendments, including not applying the new execution rules to current death row inmates; livestreaming executions on the internet; outlawing the death penalty outright; and requiring lawmakers to watch executions. All of those measures failed and were not considered by the Republican lawmakers. Other opponents of the bill brought up George Stinney, still known as the youngest person to ever be executed in the U.S.

He was 14 when he was sent to South Carolina’s electric chair after a one-day trial in 1944 for killing two white girls.

Stinney’s conviction was later thrown out in 2014. “Not only did South Carolina give the electric chair to the youngest person ever in America, but the boy was innocent,” Rep. Justin Bamberg said. Republican Rep. Weston Newton, who was in favor of the bill’s passing, noted that the debate behind the death penalty was not the place to discuss the merits of executions, saying, “This bill doesn’t deal with the merits or the propriety of whether we should have a death penalty in South Carolina.