On any given day, Deatric Edie is at one of her three jobs managing fast-food establishments. A 42-year-old mother of four, she has been working in the service industry since she was 16—starting at Papa John’s and later adding McDonald’s and Wendy’s to her work day. The routine seems unfathomable. But with salaries, respectively, of nearly $10, $8.65 (the current minimum wage in Florida) and $11, she cannot take care of her family on one job.

Clocking in full shifts at each job, Edie barely has time to sleep or see her children, who are all in their teens and twenties, or her 7-month-old grandchild. She catches as much rest as she can during mandated breaks and by sneaking furtive naps in the bathroom. “My whole life is dedicated to working.” Her jobs are all run by franchise owners, who have not offered her paid sick leave. They have also actively maneuvered to eliminate as many opportunities for overtime as possible. Having had to take unpaid time off from June to August after a COVID infection—a leave she was forced to cut short in order to keep her McDonald’s job—she is now fighting an eviction notice. “My children and I once lived in my car for a year and a half, maybe longer than that,” she says. “I don’t want to have to go through that again.”

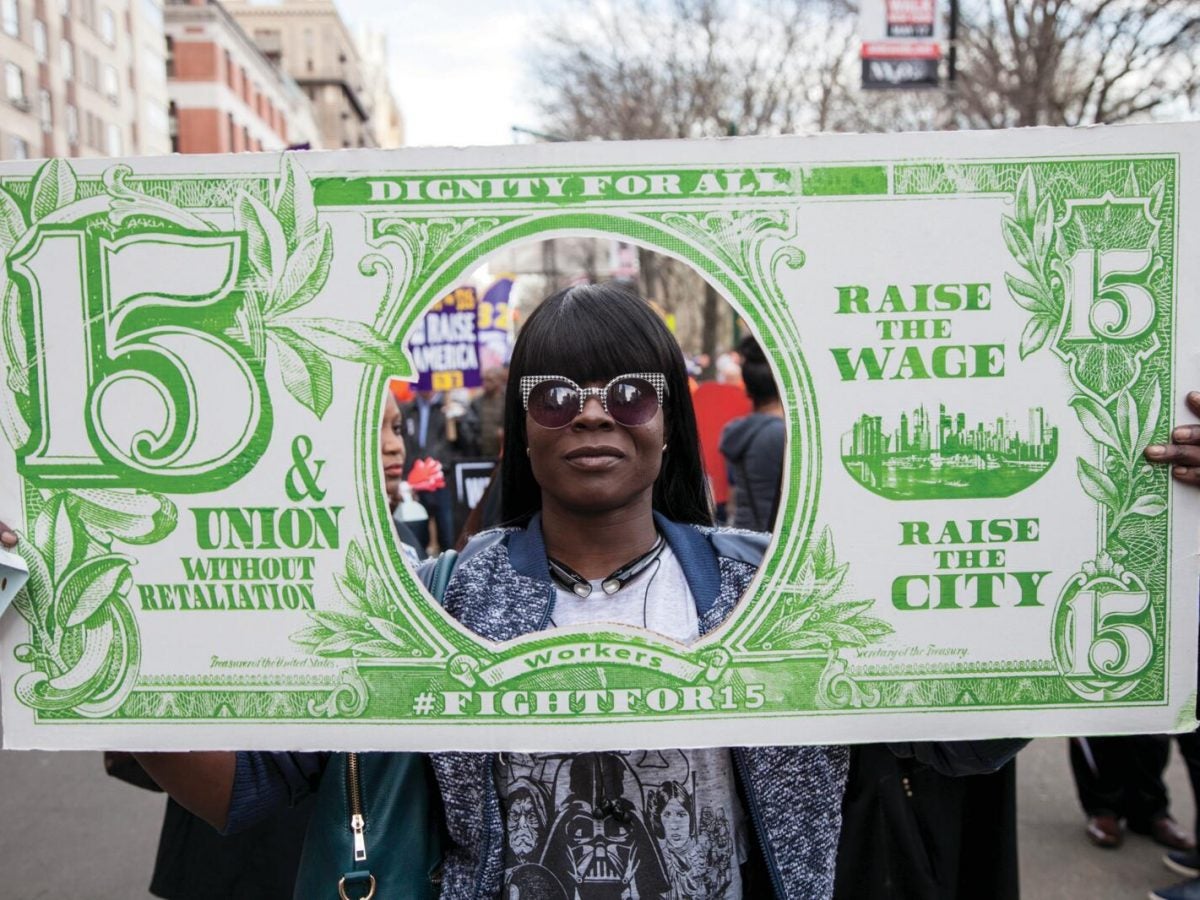

In 2019, one of her sons encouraged her to get involved in the Fight for $15, which organizes workers locally and nationally to increase the federal minimum wage. Since then, she has advocated in the streets and door-to-door to raise support for a livable wage and safe working conditions. These needs only became more critical as the pandemic worsened. Masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE) were in limited supply. Not only were coworkers clocking in with positive COVID diagnoses, but customers were becoming increasingly hostile to CDC regulations.

Edie recalls a particularly traumatic moment, when a White customer refused to wear a mask, instead throwing a drink and hurling racial epithets at her. “That was scary,” she says, still shaken. “He filmed the whole thing on camera. That moment right there, I was so close to quitting.”

Tragically, Edie’s circumstances are not an anomaly. While Black workers occupy 13 percent of all jobs, they account for about 19 percent of essential jobs that pay less than $16.54 an hour. On average, Black women in jobs that are critical to the nation’s COVID-19 recovery, from healthcare to service careers, make 11 to 27 percent less than white men in those same jobs. Black people have also had a disproportionately higher risk of exposure to COVID-19 given their prevalence in essential worker positions.

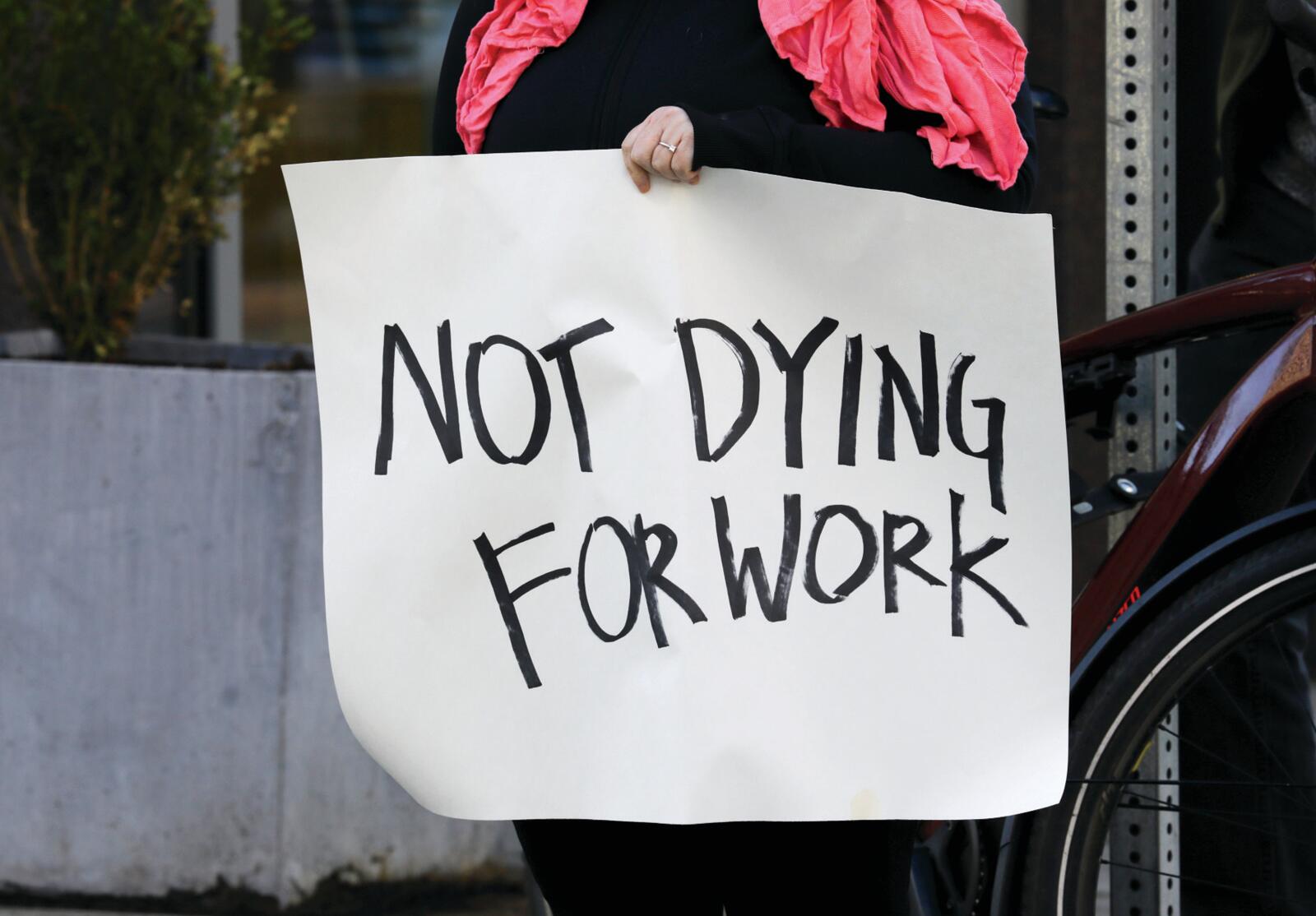

Many fast-food and drive-thru services proved to be a lifeline for middle-class professionals who were working from home during the pandemic. At one point, these franchises represented 42 percent of all restaurant revenue. Employees in these fast-food franchises across the country demanded better treatment and pay as they put their lives on the line to keep an industry afloat. “They said that ‘Black Lives Matter,’ things could change,” Edie remembers. “But they’re still not protecting us. The health and economic security of Black workers, our voices, are still not being heard.”

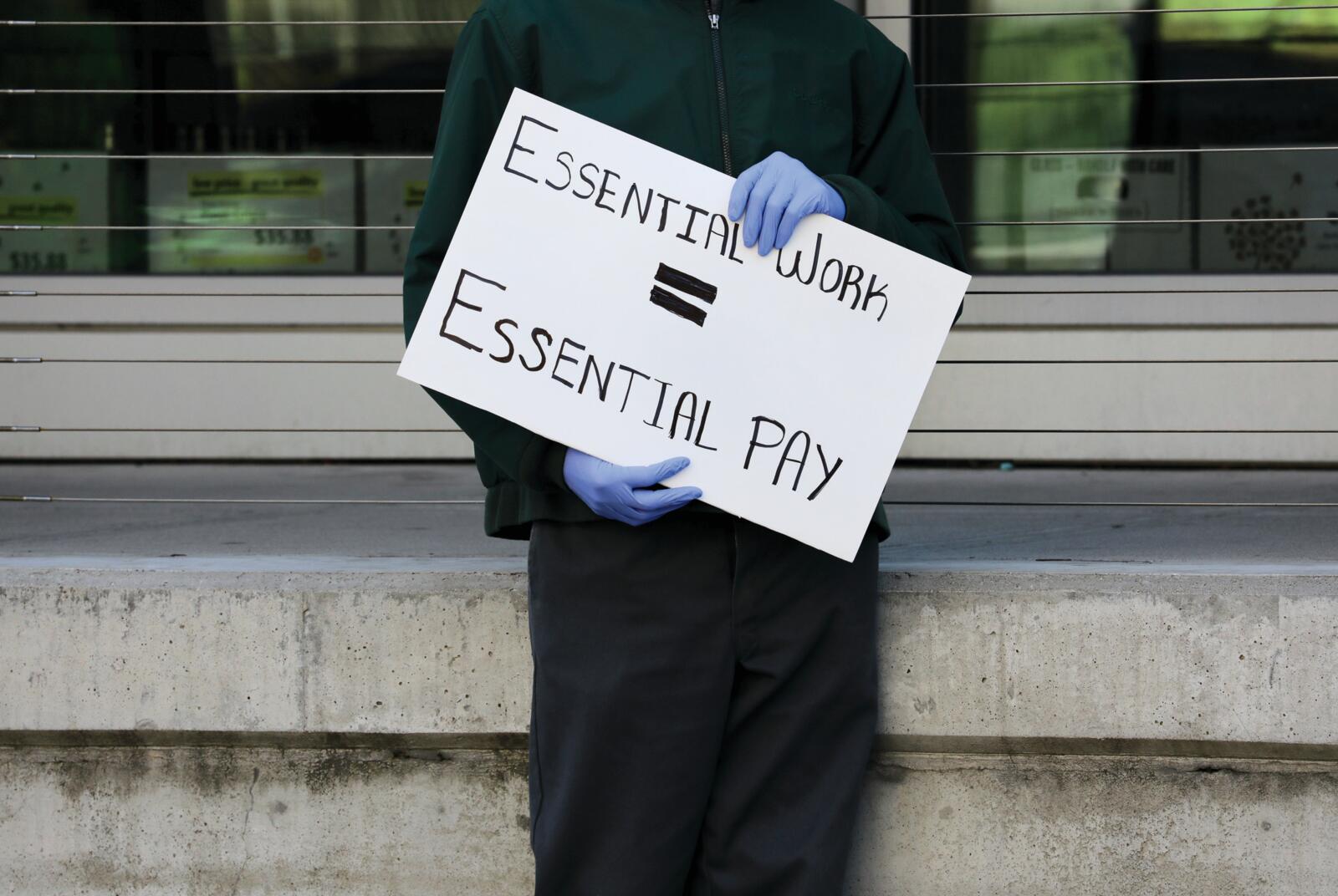

Despite being publicly lauded for their essential work, fast-food and food-delivery employees have had to continue to organize for hard-fought and often elusive victories. But the food industry is far from the only one staying afloat at the expense of its working-class employees. The use of prison labor to provide goods and services has increased in the pandemic, with the incarcerated paid less than two dollars an hour to create food items and hand sanitizer, while infection rates skyrocketed in jails and prisons. And Amazon employees nationwide have rung the alarm on the increasingly arduous work expectations in its fulfillment centers as shipments skyrocketed in the past year, creating record earnings for the company, arguably at the expense of worker safety and quality of life.

The pandemic may have heightened economic insecurity and career instability, but the foundation for these conditions are not new—they have long been enmeshed in the fabric of America’s capitalist development. From antebellum plantation slavery to corporations’ unprecedented profits over the past year, America’s growth has often been at the expense of Black workers, who continue to be overrepresented in unpaid and low-wage jobs. For example, 31 percent of Amazon’s lowest-paid workforce—its warehouse workers and call-center representatives—are Black, despite our being just 13 percent of the country’s population. The company recently touted a raise for its warehouse workers of 50 cents to $3 an hour. Meanwhile, during the pandemic, their CEO’s wealth skyrocketed 60 percent to $177 billion—and counting. By conservative estimates, Jeff Bezos makes more in an hour than one of his warehouse workers could earn in a millennium.

WATCH: Deatric Edie shares her challenges on the job & her fight to increase wages and conditions for workers like her.

With much of the nation’s white-collar workforce suddenly working from home, domestic workers and cleaning services bore much of the brunt of the economic fallout. A joint report from the Institute for Policy Studies and the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA) stated that “Black-immigrant domestic workers are at the epicenter of three converging storms—the pandemic, the resulting economic depression, and structural racism. Intersectional identities such as Black, immigrant, woman, and low-wage employee make these essential workers the most invisible and vulnerable workers in our country.” Indeed, 70 percent of the Black immigrant domestic workers surveyed either lost their jobs or received reduced hours and pay because of the pandemic.

To make matters worse, domestic workers are often treated as independent contractors, making them ineligible for unemployment benefits, despite the fact that they lack standard protections against sexual harassment and worker intimidation. Now, with the moratorium on evictions having expired, they endure the looming threat of housing insecurity as well as a national resurgence of COVID-19 among unvaccinated populations. In one of the grimmer scandals to come out of the pandemic, New York State’s gubernatorial office, led by Andrew Cuomo, revealed it had underreported nursing home deaths by almost 50 percent, putting hospice and nursing home staff at extreme risk for COVID infection alongside the immunocompromised residents under their care.

“Look at the history of domestic work,” says Celeste Faison, NDWA’s Director of Campaigns. “Most Black folks have a grandmother or an auntie that did domestic work, and that profession goes all the way back to slavery. It was enslaved Africans who worked in the house to maintain the master’s family, from being wet nurses to doing all the cleaning and cooking.”

This legacy was reflected in the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, which took pains to exclude agricultural and domestic work—industries with high rates of Black workers—an action that academics largely perceive to have reinforced segregation. “Black people were sacrificed in order for white folks to unionize, and we were left out of basic worker protections like minimum wage, paid leave, insurance,” Faison states.

Melissa, a 38-year-old home-care worker and nanny in Miami, has acutely felt the effects of the pandemic in her city, where 83 percent of Black domestic workers surveyed have been terminated. A Haitian immigrant and Temporary Protected Status recipient, she used her pay to help provide for both her young child in the United States and her mother back in Haiti. “It was a long and painful year for me,” she says. “I was let go without severance, with no plan B to take care of my 7-year-old son.”

Services like the NDWA’s Coronavirus Care Fund helped keep her afloat as she looked for employment and reckoned with the troubling reality that her field of work made her vulnerable. “I love what I’m doing, and I’m doing it with my heart, and I’m doing it with dignity,” Melissa asserts. “We are fighting to have a good wage and health coverage, but it’s a lot, because we are not considered as deserving of these benefits. I’m not as valued as I should be.”

Quyana Barrow experienced similar instability as a subcontractor for a major airline in Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport assigned to clean planes between flights. A current member of the Georgia chapter of 9to5, a national association of working women, she felt the distinct disparities in how her team was treated compared to other airline staff, from salary differentials to the lack of benefits—and all this at time when COVID-19 protocols demanded more rigorous attention to how aircrafts were being cleaned.

“We were paid $9.25 an hour, and then if you became a team leader you would get a dollar more,” Barrow shares. “People perceive Atlanta as a place where you can get more value for your dollar, but even here, prices are going up. So if $10.25 was a living wage a year ago—which it wasn’t—right now it’s much worse.”

For many of Barrow’s co-workers, however, that paltry paycheck was the only source of income for their households. And, as flights were canceled, workers were sent home early, furloughed or dismissed altogether. With employees relying on management to reaffirm their unemployment eligibility weekly, unionizing interest began to stir among both longer-term workers to recent hires. The momentum was short-lived, however, as people feared retaliation for their organizing efforts. “People started to call in those organizations to management, and the bonds you thought you had started to fall apart,” Barrow says.

Over the last year, the various movements to protect Black lives that were sparked by Black people being killed by law enforcement, expanded from discussions about surviving state violence to promises of workplace equity across the board. Most of those commitments, however, focused on middle class, white-collar positions in professional sectors such as media and entertainment. There was some deserved acknowledgment of the herculean efforts of healthcare workers in the face of instability and fear, but other working-class people who fought for acknowledgment and recompense were left in the margins.

The increasing collective efforts toward recognition are at the mercy of political perceptions about the necessity and value of “unskilled labor,” jobs that also come with a high level of precarity, surveillance, and risk of retaliation from their employers. Workers like Edie, however, remain unbowed. Along with the Fight for $15, she participates in worker-led movements like the 2020 Strike for Black Lives to help show how the fights for racial, economic, healthcare and immigration justice are interconnected.

“I always take my children and my grandson with me,” she says. “I want them to see what’s going on in this world.” For Edie, this is not a fight she can afford to abandon: $15 an hour would allow her to go back to working just one job, giving her the time to reinvest in herself and her family and potentially take a vacation. “I want to be able to take my grandson to Disney World,” she remarks wistfully.

Her unsustainable routine has taken an understandable toll on her mental health, with limited resources available for her outside of medication. “I don’t know if I can ever get over this situation here,” she sighs. “No matter how many times I say I can do it, I feel like I’m lying to myself, but I’m going to keep saying it because I have to be strong, and I have to look out for my children.”

With her two sons, now 19 and 25, that means trying to keep tabs on their whereabouts, and managing her fear for their safety whenever she hears gunshots in the neighborhood. Her daughter Latrice was enrolled at Florida Atlantic University but was forced to drop out when her financial assistance ran out. She is currently at home, trying to figure out a path back to post-secondary education in a world that actively undermines her family’s economic mobility.

Despite the enormous challenges of her circumstances, Edie remains determined to keep on keeping on. Fight for $15 has given her the momentum to fully engage the battle. “This is my life, this is what I go through,” she declares. “If anyone is willing to help me up, hey, I’m here, I’m gonna take the help. My story is real. My tears are real.”