As an artist and alumnus of the historically Black male institution, Morehouse College, I was dismayed, ‘though not surprised, to learn of their recent decision to ban cross-dressing on their campus, along with do-rags, sagging pants, and headwear (grills?), as part of its new “dress code.”

Morehouse is a private institution that has worked tirelessly at uplifting the image and esteem of African-American men for generations and thus has every right to enforce the codes of conduct and expression that it sees as beneficial to its student body, yet its conservative/traditionalist ideology is sometimes at odds with the progressive awareness that it would seemingly hope to instill, or even more importantly, nurture in its students. Furthermore, its stride to maintain a highbrow mystique seems to lie solely in its preparation of young men to enter the Fortune 500 or some ministerial fellowship, with little and waning interests in the arts or the importance of creative expression.

My first day at Morehouse was the last day I combed my hair. I couldn’t wait to twist and lock what my father had insisted I comb, while sleeping in his house. I knew that my time away from church and home was especially suited to be just that: My time. And I planned to use it wisely to express and explore all that I was on the verge of discovering. Here was where I ‘d be given the space and, perhaps, the inspiration to question aspects of my upbringing, harness new disciplines, pursue my passions, and, quite simply, mature. I didn’t find it particularly bothersome when, during that first week, my freshman brothers and I were told, “Morehouse men do not wear locks,” that I’d have to cut my hair to sing in their prestigious Glee Club (this about the same time that my father told me I should cut my hair to be in my sister’s wedding), and that, although I would declare myself a philosophy and drama major at Morehouse, I would have to take all of my drama classes at another historically Black institution, Spelman College, across the street, because Morehouse (although it offered the major in its course book) had no drama department of its own.

No drama, no dreadlocks, did little to curb my enthusiasm or stop me and other classmates from expressing new growth through hair and hip. Young men going to school to find themselves, who, in turn, find themselves suppressed by the short-sighted mandates of an authority that has a simple task of nurturing rather than negating, will simply blossom despite rather than because of their administrative elders. And, although being pulled aside by a school dean and asked how we expected to fair at a job interview might officially intimidate some, for others, like myself, it simply confirmed that they were old school and had not yet come to accept the world that we were crafting. This was not new news. We had all grown up with parents who questioned our musical taste and renderings reflected through fashion and slang. A confidence and swagger that simply didn’t exist in the era of our elders defined our generation, so we were used to explaining “La Di Da Di” to frowning grandparents and professors.

I, personally, had no problem leaving my all-male campus to enter the all female institution across the street for drama classes. It was on Spelman’s campus that I acted, danced, recited poems, added formative layers to my creative process, and even received compliments on my hair. While Morehouse in both real and symbolic ways represented more and more of the world I had gone to college to escape; a world where I saw hypocrisy and tradition intertwined, then neatly placed under the bureaucratic robe of authority.

The fact that my college seemed unprepared for me and the generation of artists that I’ve grown to be a part of says a lot about the social climate that followed my graduation. A time when hip-hop aligned itself with bankers and gangsters and would-be artists found greater merit in referring to themselves as businessmen than as artists.

The transformative power of art was harnessed and used to knock down the walls of the music, fashion, and film industries, while the art itself suffered. Music no longer pushed against the status quo, rather, it upheld it. Movies amounted to soup’d up church plays. Public schools lost their music and art programs. Colleges and universities, such as Morehouse, found bank and business CEOs to manage their affairs and became little more than product assembly lines turning out the latest in a conservative male model that simply saw art as escape.

Freedom of expression is Art Appreciation 101 and a tenant deeply rooted in American democracy. The fight for those freedoms has placed American arts and artists in a category all their own. The role that art plays in shaping American society is unparalleled and quite often unpredictable. And the role that African-American artists play and have played in defining exactly what American art is, is undeniable. These lessons, which for me, came as a male visitor on Spelman’s all-female campus serves as the basis of the sort of dialogue that has all but skipped a generation born after the Black Arts Movement.

So what happens when prestigious institutions, like Morehouse, overlook the value of expression and instead choose to align themselves with the merits of an elite business school? And what do the cross-dressing students that were recently made to change clothes by Morehouse’s administration have to do with my wild hair and me? Everything. Until these institutions acknowledge the inseparable links between freedom and expression, the same forces that suppress free thought and progressive change will suppress art and the evolving consciousness surrounding it. And when our universities align themselves with forces that suppress free thought and progressive change, they get more like churches and less like schools.

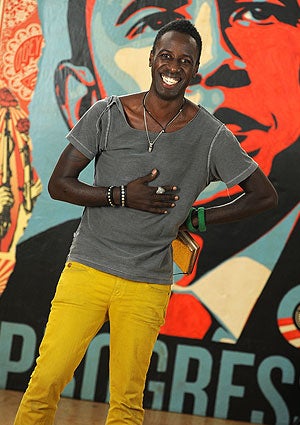

All this to say: I decided to wear a skirt to my alma mater last week and they weren’t too happy about it.

Diligently Southern in its hospitality, the administration congratulated me on my merits and asked me kindly to leave its premises. They said that they had to enforce their new dress code on campus so that their students would follow suit. As I was leaving, an openly gay student government member approached me in a suit. He told me that he exemplified how a Morehouse man should dress because he was prepared. “Prepared for what?” I asked. “Prepared in case someone wanted to interview me for a job.” he said.

Before speaking he had signed the waiver that the cameraman beside me was holding. He knew he was being filmed as part of a documentary that Afro Punk was making as we crossed the country. “Perfect!” I said. “You get the job.”