Much of the country has extolled the triumph of this nation getting its first Black woman on the United States Supreme Court. As it should.

But the beauty of Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation is also its pain. The weighty pain of such an important “first” this late in the American story.

Because where there is a first, there’s all the void that came before it. A void that goes back to the Supreme Court’s inception in 1790.

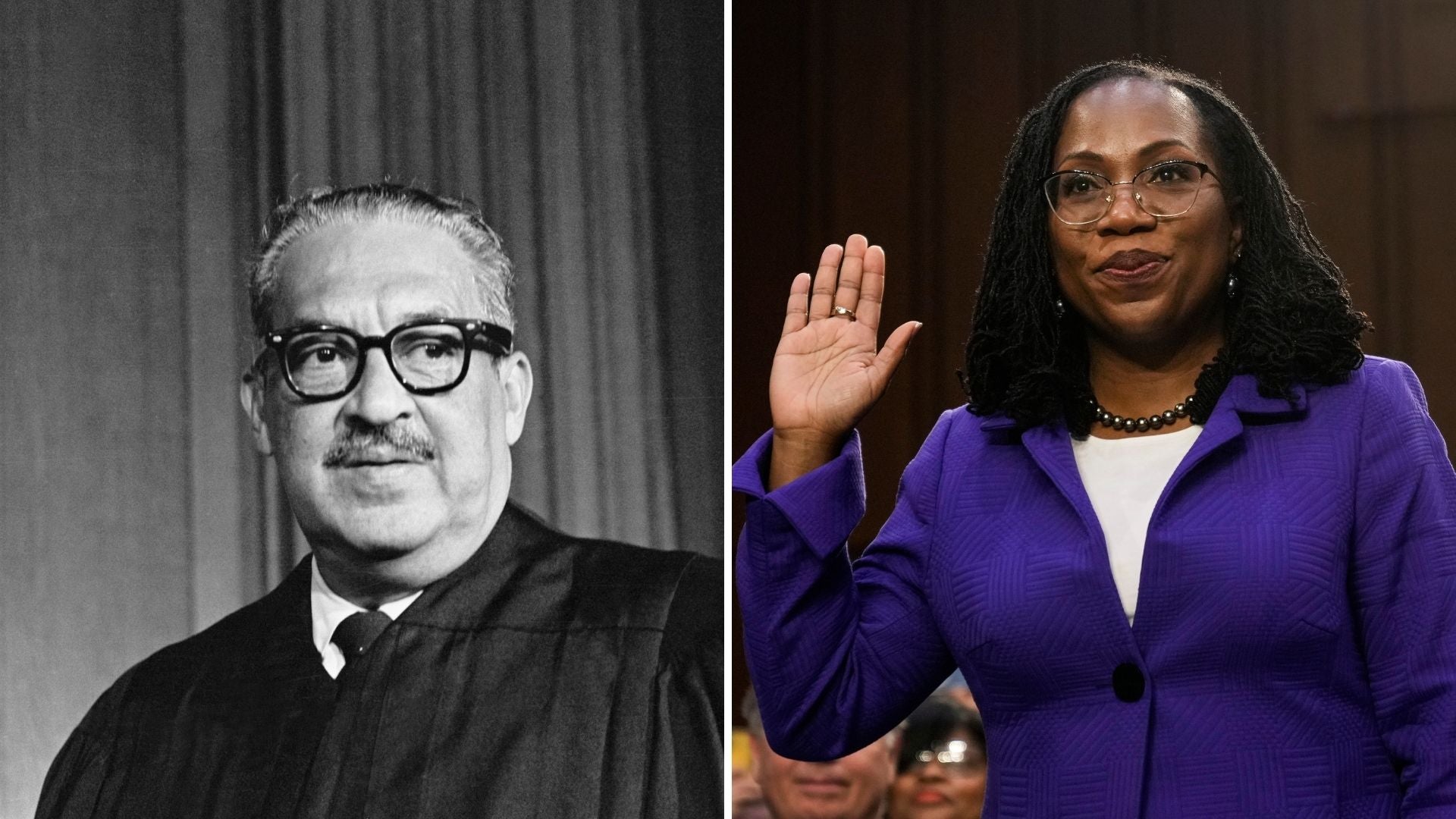

I entered law school in 1992. I left the profession of newspaper reporting because I believed the law was a better path to societal justice and equity than journalism was providing. Although not consciously done, I was applying for and entering law school at a particularly important point in cultural and jurisprudence history—Thurgood Marshall—the first Black Supreme Court justice had retired in 1991. So, literally, as I was putting my packets of law school applications together, Clarence Thomas was nominated for the vacancy, and the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings flooded our airwaves. Like many others, I was both riveted and appalled by how a Black woman attorney (something that was a unicorn to much of America) was having to play a horrible part in what the legacy of Black people on the Supreme Court looked like.

The rest is history. Justice Thomas, as the second Black person – the second Black man was confirmed to be on the court.

But that intersection of history wasn’t done. In January 1993, the second semester of my first year of law school, Thurgood Marshall died. Someone who was larger than life, whose face was probably imprinted in the consciousness of much of Black America was gone. Even before he sat on the biggest judicial bench in the land, he argued before the Supreme Court the famous Brown vs. the Topeka Board of Education case that desegregated schools. Justice Marshall’s shadow hovers over one of the most important cases in law and life. And to be a Black law student at the time, I think there was a little wind knocked out of all of us at the news of his passing.

There are a million things I can’t remember between now and almost 30 years ago. But if I got in my car and drove six hours west to the University of Missouri School of Law in Columbia, I could go straight to the very room where the Black Law Students Association held a candlelight vigil for Justice Marshall, and even remember about where I stood as one of my classmates spoke. I don’t remember the words, but our collective loss was palpable. As I said in a tweet the day that Judge Jackson was confirmed, a candlelight vigil for Justice Marshall seemed fitting because it felt as if a light had gone out in the world. Since I was a little older than my law school classmates, that means that for most of the Black law students at that memorial, Justice Marshall had been on the Supreme Court their entire life.

As a first-generation college graduate, I graduated from law school in 1995 and practiced law for eight years. I never regretted leaving the practice of law—despite embarrassing bouts of near poverty from doing freelance work that was less than stable, plus enduring relentless questioning from others in those early years about how I could dare to leave law. And one of the reasons there have been no regrets in almost 20 years is because I left a profession where people who looked like me weren’t plentiful enough or high enough in the industry to ever make me feel like I belonged. And frankly, I didn’t love the legal profession enough to keep fighting the good fight. Money was never my motivation to enter it and money wasn’t going to be the trap to keep me doing it.

And, it turns out, that decision to leave wasn’t as unique as one might think. In a very recent study from the American Bar Association, 70 percent of attorneys who were women of color (so not just Black women) had left or had considered leaving the practice of law. The reasons are varied and it’s obviously more than just the work is challenging and brutally demanding.

For Black women specifically, I’d argue that the profession demands that you give so much of yourself to it, yet leaves you little indication that you will remotely have a shot at the same career trajectory as your white male counterparts. And while that is true of every single profession and career path in America, that’s a particularly daunting realization to come to about the one profession that theoretically is supposed to keep all others in check. Most of the white male attorneys that I know still practice law, while most of the Black women attorneys I know have left the practice.

When sitting Supreme Court Justice Justice Stephen Breyer announced that he was retiring, leaving President Joe Biden to nominate his replacement and that the replacement would be a Black woman, I had a knot in my stomach that reminded me of why I left the law in the first place. As I said to many a friend, I had zero problem with him having the objective, I just wish he would have done it without broadcasting it. The objectification of Black women for the gains of others, and then having to pick someone exemplary and stunningly exceptionally qualified to ward off attacks of bias and discrimination against white men is a criticism that will happen anyway. So instead of just nominating high-caliber legal minds for consideration – all of whom could have easily been Black women – we had to sit with the backlash, combined with the confirmation proceeding and its particular stew of partisan ugliness. And, yes, as more than one person has reminded me, it was a campaign promise, but it still bothered me. In the end though, as I said, it probably didn’t matter because the criticism was going to happen no matter how he handled it.

I’ll admit that I couldn’t watch the confirmation proceedings for Judge Jackson. It wasn’t just painful to watch as a Black woman, it was painful to watch as a former attorney. But having the news clips pop in my social media feed and on the television news and on the radio news station where I work, didn’t insulate me. My fear was justified.

Although what she went through was on a level a thousand times what I or any of my sister lawyers went through, it was representational. Law is still the ultimate white boys’ club, and for a Black woman attorney, you are usually never enough and almost always too much. Even if you are the most pleasant, likable woman like Judge Jackson seems to be, who also has killer credentials, starting with her graduation from Harvard Law School, if you are a Black woman, you are still not the prototype of what people think of when they think lawyer. And never when they thought of the Supreme Court.

Justice Marshall kicked down a huge door. No doubt. But it took 55 years for a Black woman to squeeze through that same door. Does the average attorney consciously and regularly think about the Supreme Court? No. There are entire areas of law, where attorneys never think about the big bench. Yet, their presence, their power, their presiding over the precedents looms large over the very fabric of how our society is shaped.

And lawyers know that. They know that while legislators write laws, the lifespan of a law or interpretation of that law can change if the right set of lawyers makes the right set of arguments to the nine Supremes.

The day of the vote for Judge Jackson’s confirmation was the first day that knot in my stomach could start to unclench. That’s not true. It started when I saw the photo that went viral of her daughter looking at her with such pride. That look of pride was one shared by people all over this country, and not just Black women or Black lawyers or Black law students.

There is not a doubt in my mind that while Judge Jackson – who will soon be Supreme Court Justice Jackson – is an inspiring and unique woman and jurist in her own right, she will continue the legacy started by Justice Marshall. Her experiences in all walks of life, including her unique vantage point of having been a public defender, will bring perspectives and conversations to the Supreme Court that have literally never been brought before.

Law is very much about what value systems a democracy holds dear, and what values are preserved and shaped. Ketanji Brown Jackson didn’t just get a good job, she got a lifetime appointment to the highest court in the land.

But representation also matters. It provides hope to current and future generations of Black women students and Black women lawyers who can now see their faces reflected in the most enduring, powerful institution in the land. The conversation changes when who is in the room changes.

While I can still vividly remember the candlelight vigil we had for Thurgood Marshall, when I saw, Ketanji Brown Jackson, at her confirmation celebration, noting that for her family it was just one generation from segregation to the Supreme Court, I couldn’t help but think that today, she is the candle.

Michelle Tyrene Johnson is a former attorney, a public radio talk show producer, a playwright, and the author of the book “Working While Black: The Black Person’s Guide to Success in the White Workplace”.