In the inaugural issue of ESSENCE, in May 1970, journalist Gilbert Moore highlighted some of the era’s most important Black women leaders whom he described as “bound together by race, by sex, by impatience, by the simple yet complex proposition that Black people shall have dignity in America, in the world.”

Entitled “Five Shades of Militancy,” the article featured longtime activist and civil rights icon Rosa Parks; Black Panther leader Kathleen Cleaver; Barbara Ann Teer, the artistic visionary behind the National Black Theatre in Harlem; political pioneer Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman in Congress and the first major-party Black candidate to make a bid for the U.S. presidency; and the women of the Nation of Islam. The accompanying images were shot by none other than famed photographer Gordon Parks and his son, Gordon Parks, Jr.

At the time this piece was published, the concept of Black militancy was nearly as ubiquitous as today’s wokeness, or social justice activism, though perhaps it was infinitely more polarizing. “In the endless human propensity for generalization, for categorizing people, we have arbitrarily divided Black people into three categories—moderates, militants and Toms,” wrote Moore. “It facilitates study and conversation; it is convenient.”

If Toms were seen as committed to pleasing the White forces that maintained control over Black life in the U.S. and moderates were considered too dispassionate or complacent to pick a side, militants were the women and men who believed that Black liberation was worth fighting for and committed themselves to that fight. The term militant was most often associated with groups like the Black Panther Party and agitators such as leftist organizer Stokely Carmichael, the Father of Black Power.

Fifty years later Black women continue to be at the forefront of any and all substantive movements for civil rights and justice for marginalized people in the United States. The barriers faced by our foremothers and those they fought for have not been vanquished. Racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, transphobia and socioeconomic disenfranchisement continue to plague our communities, along with the refusal of the world around us to affirm and constructively support the leadership of Black women.

Nevertheless, the freedom fighters of today are as militant as our foremothers as they work to see that our people are treated with a fairness and dignity that we have yet to experience on these shores. Here we salute some of the women who have made it clear that, as Moore wrote, “whatever is required to obtain that dignity shall be done. And whatever forces combine to deny that dignity shall be removed forthwith.”

My career has been dedicated to exposing the architecture of racial inequality.”

—NIKOLE HANNAH-JONES

A Modern-Day Warrior for Truth

Nikole Hannah-Jones has garnered international acclaim for her critical work on racial inequity in America’s public schools. The New York Times Magazine staff writer has received a number of distinguished honors for her dogged reporting on the long history of segregation in housing and schools, including a National Magazine Award, a Peabody and the celebrated MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, known as the Genius Grant. In 2015 Hannah-Jones cofounded the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting to provide mentorship, training and support for investigative reporters of color, who are grossly underrepresented in newsrooms across the country.

The 43-year-old was the driving force behind the Times’ critically acclaimed 1619 Project in August of last year, marking 400 years since the first enslaved Africans were brought to the shores of what would become the United States. The multimedia commemoration traced the genesis of the disenfranchisement that Black people face in the present day to the system of chattel slavery and the deliberate racist strategies that sustained it.

The 360-degree exploration included essays, photographs, poetry, short fiction, a podcast and live events headlined by some of our most impressive scholars, writers, historians, politicians and artists, and it led to a related curriculum developed in conjunction with the Pulitzer Center. The special New York Times Magazine issue dedicated to the 1619 Project would be reprinted so many times that hundreds of thousands of copies were ultimately sold.

Hannah-Jones is a modern-day warrior woman, cut from the same cloth as the pioneering journalist for whom her organization is named. While Ida B. Wells held up a magnifying glass to the horrors of lynching, refuting pervasive myths about Black male criminality and properly contextualizing the crimes as an effort to maintain White supremacy, Hannah-Jones has similarly worked to disrupt narratives that present African-Americans as responsible for their own struggles.

School segregation was one of the definitive issues of the Civil Rights Movement, and fallout from that policy remains. Yet a cursory exploration of mass media’s coverage of issues related to racial justice might imply that inequality in education is no longer a problem. Nor does the media adequately reflect that violent policing and mass incarceration are issues of pressing urgency among Blacks in the United States. Hannah-Jones attributes that erasure to the fact that a “very visceral reaction” of our community to the death of yet another Black citizen at the hands of the police isn’t shared by everyone. “White Americans are not impacted by us working on police violence,” she explains. “It doesn’t affect them in their personal lives. They may feel badly about it, but it has no real impact.”

The persistent debate over the value of school integration, in terms of how Black children may or may not benefit, must include what’s involved in bringing those conditions to fruition in the first place. “There is a feeling of, why are we going to keep fighting and begging White people to send their kids to school with our children?” Hannah-Jones says. “And I understand that weariness.” But as the Iowa native points out, we simply don’t have the luxury of giving up. “I feel like my whole career has been dedicated to exposing the architecture of racial inequality,” she says. “Not just to document that it exists, but to show how it was created and how it’s still intentionally maintained.”

Fighting for Environmental Justice

While school segregation may fail to sustain the attention it deserves, environmental racism is, at times, a mystery in plain sight. Like Hannah-Jones, Dorceta E. Taylor has spent much of her career exploring how the conditions experienced by Black people in the United States are indicative of our environment. The Jamaican-born sociologist is best known for her research and writings on environmental justice and racial disparities in the world of ecology. Her works include 2009’s The Environment and the People in American Cities: 1600s–1900s, one of the first exhaustive looks at the intersection of race and ecological inequity, and The Rise of the American Conservation Movement, a social history that outlines how race, gender and class inform the populations that will benefit or be sacrificed in the name of conservation and sustainability efforts.

“Black women are everyday environmentalists; we just don’t get the headlines too often,” wrote Heather McTeer Toney of the Moms Clean Air Force in a Times op-ed last year—a sentiment Taylor echoes. “If you look at the South Side of Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans and New York City, you see a lot of Black and Brown women who are fiercely fighting, educating themselves and their community in tremendous ways, and empowering the youth, all without a lot of resources,” says Taylor, who serves as the director of diversity, equity and inclusion at the University of Michigan’s School of Environment and Sustainability. “African-Americans have been doing environmental justice for a long time. We just didn’t call it that.”

As examples, she points to the lifesaving efforts of African-Americans in response to the 1793 yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia and the early work of W.E.B. Du Bois. “He was actually talking about what we now would think about as housing—environmental issues around environmental degradation,” Taylor says. “But again, he wasn’t using that terminology.”

We don’t have to look far to see the impact of environmental racism in our lives: “We can start at home, not just looking at the products that we use around the home, but also looking at where communities of color are located,” Taylor notes. “Start by asking, ‘Why does the freeway run right through the middle of my Black community?’ ”

In addition to identifying the historical impact of environmental racism and the flash point moments that manage to make it to the news, Taylor urges us to be keen observers of the less obvious examples around us.

For example, a lack of access to basic utilities can have devastating ramifications—a fact that begins to explain why so many Black families struggle to pay these bills. “Electric rates are highest in segregated Black communities because of certain rate structures,” she explains. “And taxes are higher per unit of housing in these Black segregated communities, too.” All this can lead to some families being unable to afford to keep their homes. Worse, the resources made available to these communities typically fail to reflect what residents pay to remain in them.

Young people don’t make the mistake of thinking that environmental justice is not as important as fighting against police brutality and poor schools.”

—DORCETA E. TAYLOR

Taylor praises young people for “connecting the dots” and examining “everything from residential segregation to pollution to the destruction of communities with facilities or freeways or dumping to energy, climate, health and equity injustice.”

Young people, she says, understand that all these travesties are part of a continuum, rather than a series of isolated challenges: “They don’t make the mistake we’ve made in the past of thinking that environmental justice is not as important as fighting against police brutality and poor schools. The young people understand that the environment is just as important, and they’ve become very active around it.”

Taylor makes a point of uplifting powerful environmental justice work taking place in cities across the country, including Detroit’s seven-acre D-Town Farm; West Harlem Environmental Action; and Blacks in Green, a Chicago-based national network dedicated to land stewardship and educating folks about the harms of climate change and the benefits of a new green economy. “They’re doing restoration work, cleaning up the neighborhood, creating gardens, creating farms, reinvigorating Black living spaces, artwork, you name it,” she says. “And that’s going on all over the country.”

Blacks in Green activists cite the Underground Railroad as a source of inspiration for their work, making a connection between their efforts and that of its most famous conductor. “Harriet Tubman had to have had a significant amount of environmental knowledge to do what she did,” explains Taylor. “Escape, escape safely, bring other people along, go back and get more. Yet we tell her story as simply a story of overcoming slavery.”

While Tubman is indeed best known for helping hundreds of enslaved Africans flee the brutality of the plantation and find freedom, she was also a leading abolitionist, fighting to destroy an abusive, dehumanizing system of forced labor and bondage—a role that Taylor believes is completely comparable to modern-day efforts to promote the right of our communities to live free of environmental injustice and targeted discrimination.

Demanding Fairness at the Polls

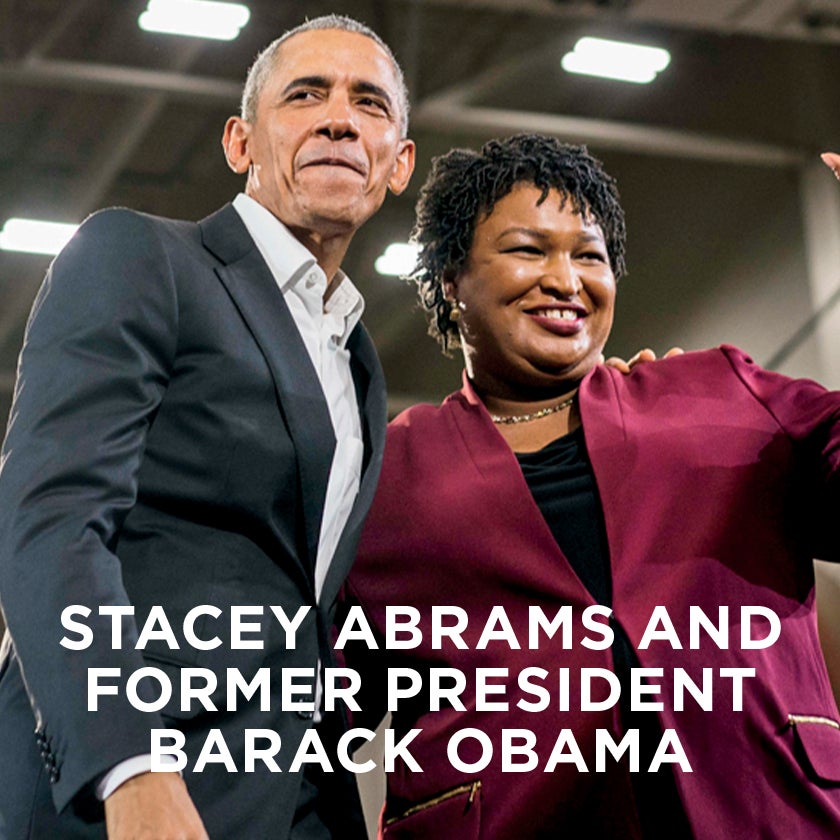

Stacey Abrams embodies the spirit of the late Shirley Chisholm’s efforts to effect radical change from “inside.” Abrams spent 11 years in the Georgia House of Representatives, seven as minority leader, before the historic 2018 campaign for governor that would establish her as one of the most important figures in the Democratic Party. Abrams was the first Black woman to become a major-party gubernatorial nominee, and she received more votes than any prior Democrat in Georgia’s history.

However, she lost by a narrow margin to Republican Brian Kemp, who, as the sitting Georgia secretary of state, was also responsible for supervising the election. It is widely believed that Abrams’s defeat did not take place at the polls, but instead was the result of rampant voter disenfranchisement, including Kemp’s documented effort to purge well over a million voters from the rolls during his tenure as secretary of state.

Injustice is not a new phenomenon. Therefore our obligation is to never waver in the battle to defeat it.

—STACEY ABRAMS

Kemp then put an additional 53,000 registrations on hold just one month before the election. Abrams both refused to concede defeat and sued the Board of Elections. She subsequently decided to take on the pervasive inequities in our electoral system formally. Last summer she launched Fair Fight, a nonprofit dedicated to ensuring fairness and accuracy not only in our state and national elections but also in the upcoming 2020 census.

“Injustice is not a new phenomenon,” says the Wisconsin-born, Mississippi-raised politician. “Therefore our obligation is to never waver in the battle to defeat it.” She credits her parents with instilling a sense of obligation to work on behalf of the greater good: They always reminded us that no matter how little we had, there was always someone with less, and it was our duty to serve that person. That upbringing inspires the work I do.”

The continued need for African-Americans to fight for voting rights is perhaps one of the nation’s cruelest realities. Since 2008—the year Barack Obama was elected as the nation’s first Black president—red states across the country have taken measures that have made voting more difficult for populations that typically cast ballots for Democrats: Black folks, the elderly, college students and so on.

A 2014 Supreme Court decision stripped away one of the most important measures of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which had required lawmakers in states with histories of discriminating against voters of color to obtain permission before changing local voting rules. “Voting is a critical power, one that is being stolen by those who were elected to defend it,” Abrams says.

“Through our votes, we have the ability to shape the future of our communities, by electing leaders who share our values and respect our contributions. To reclaim our power, we must participate in every election, from judge to state legislator to president, and we must be counted in the 2020 census.”