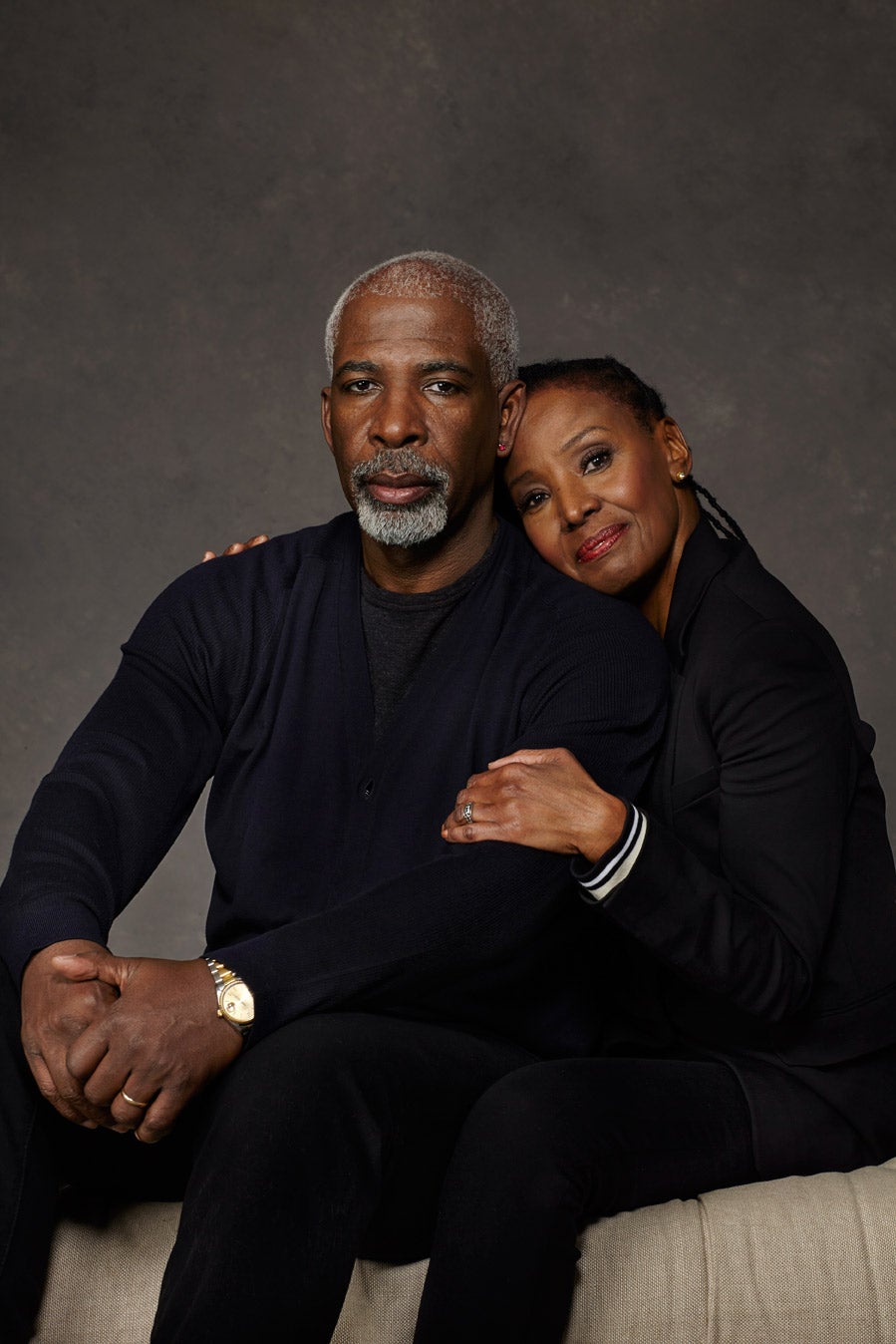

Sitting side by side on a leopard-print couch in their sun-filled waterfront house in Sag Harbor, New York, Barbara Smith and Dan Gasby look every bit the glamorous couple who built the B. Smith lifestyle brand. At 66, Smith has a face and figure women 20 years younger could envy. It’s easy to imagine her as the model she was, gracing five ESSENCE covers and becoming one of the first Black women on the cover of Mademoiselle. Tall and handsome, Gasby appears as fit as in the wedding picture, taken 23 years earlier, displayed among the family photos on their coffee table. But little about their lives is the same since Alzheimer’s began its assault on Smith’s brain. Now their days revolve around two missions: one public, to rally forces against an illness that disproportionately attacks Black women; one deeply intimate, to cherish what the disease has not yet taken from them.

“You live in the moment,” Gasby says at the couple’s Long Island home. “You give up the feeling of, This is unbearable or I can’t accept this or I feel this sense of loss. You just move on. You have to do that, because with Alzheimer’s there’s no negotiating.”

B. Smith Reveals Battle with Alzheimer’s Disease

No negotiating. And for them, no hiding. When Smith was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in the spring of 2013, they committed to using their story to combat the ignorance, apathy and stigma surrounding the disease. B. Smith, the lifestyle maven whose empire once included cookbooks, a magazine, licensed home products, a syndicated television show and restaurants filled with A-list celebrities, would step into the spotlight one more time—as the face of Alzheimer’s.

The couple open up about their experience in a remarkably revealing new book, Before I Forget: Love, Hope, Help, and Acceptance in Our Fight Against Alzheimer’s (Harmony, $25), written with Michael Shnayerson. It is a tale at once heartbreaking and heartwarming, showing the two grappling with loss in what looked like a charmed life. The book intersperses candid, poignant details about how the disease has transformed their relationship, information about promising medical research and practical advice for staying sane as a caregiver.

“Going it alone doesn’t make you a hero,” Gasby writes. “It just wears you down and burns you out.”

The two are equally candid in person this late fall afternoon as they talk about their continuing journey to come to terms with the disease.

Smith still radiates the warmth that has long enchanted fans and close friends. She can be funny and playful, especially delighting in her devoted 110-pound Italian mastiff, Bishop. But sometimes the words to express a thought elude her, or the thought itself goes slightly off-kilter. She struggles to describe the feeling before she was diagnosed, when mood swings (angry outbursts are a common Alzheimer’s symptom) and forgetfulness signaled something wasn’t right.

“When that started, I had my times of being maybe not so nice, you know?” she says. “You’re like, in a basket. When am I going to get out?”

This once-equal partner in business and in life now lets her husband do most of the talking.

Talk he does, with a persuasiveness honed over decades as a media executive and the urgency of a prophet compelled by a message he never wanted but can’t let go.

Gasby calls Alzheimer’s a “twenty-first century civil rights issue.” And he has the statistics to back it up: Some 5.3 million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s; almost two thirds are women. Even more striking—Black folks are twice as likely as Whites to get the disease. Ten percent of us over the age of 65 have it. Half of African-Americans 85 or older suffer from the illness.

“This is a devastating disease that is wreaking havoc within the Black community,” Gasby says. “Black lives matter? Black health is what is going to make Black lives better.”

Gasby prescribes a multipronged solution that includes a greater investment in Alzheimer’s research, education about diet and exercise habits that might ward off or slow the progression of the illness (diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease may increase susceptibility), and funding for testing to detect the disease earlier.

Smith was diagnosed after the couple paid for a test that involved injecting radioactive isotopes into her blood, which traveled to her brain, where a scan revealed clumps of amyloid plaque that act like potholes to impede the path of neurons that control cognitive functions. The cost, which their insurance didn’t cover, was $4,000—out of reach for many if not most.

“We also need to be better represented in medical trials,” says Gasby, who points out that even subtle differences in genetic makeup may cause drugs to be more or less effective for certain groups. To African-Americans wary of volunteering for experiments because of the history of racism in research, his message is simple: You owe it to the next generation to get over it.

“What a tragedy it would be if 25, 30 years from now, the group of people who still have the highest incidence and feel the greatest impact [of Alzheimer’s disease] were Black people because they didn’t have enough of a sample base to find out which drugs might work for them,” he says.

Gasby is fighting for a different kind of future. A future in which Alzheimer’s no longer has the power to decimate African-American families. One in which it is, if not eliminated, preventable and treatable.

He fights, though he knows that future will likely come too late to save his wife.

At home, he wages a moment-to–moment battle to keep her happy and safe. A tough balance, as safety comes at the cost of the independence she still craves. A recurring argument had flared just that morning.

“She still wants to drive, but she doesn’t know what day it is, she doesn’t know what year it is,” Gasby says.

By afternoon all seems forgiven. Smith looks at her husband with affection as he speaks. She laughs at his humor and interjects short comments affirming or expanding on his sentiments. Once she praises, “He has a way with words.” Once, after he holds forth passionately on Black health, she claps.

Asked if her husband ever frustrates her, she replies, “Not too much. No, he’s pretty good. Aren’t you, Dan?”

Gasby gently calls her on it. “Honey, look, I do things that frustrate you. When I tell you that you can’t drive your car, you get really angry.”

“Why did you have to say that?” she asks in the humorously exasperated tone of a long-married wife.

“Because we’re being honest.”

And honestly, Alzheimer’s can be brutal on a marriage. Gasby is still adjusting—from being lover, partner and best friend to being a full-time caregiver responsible for everything from making sure his wife is appropriately dressed to cooking to making business decisions. But the practical demands pale in comparison to the emotional toll of living with someone who may love him in one breath and hate him in the next.

“I treat our relationship the way you fly in an airplane. When the pilot comes on and says, “We’re about to experience turbulence,” you tighten the belt, you know that it can get bumpy, but the plane will land. It might not be pleasant, and ten minutes can feel like an hour when it’s dropping.”

He copes by snatching small breaks to call a friend or just be alone for a short time. And he’s learned to separate the disease from the woman he loves.

“She is inside more beautiful than she is on the outside,” he says. “She is what I view as a model of what people should be. She is so damn decent and looks for the good. She looks for the light in people to help bring it out. She can make an SOB just the nicest person. That’s her gift.”

For Smith, coping means relishing the simple joys—like walking with her husband and her massive dog on the beach in front of their home—and knowing she still has something important to contribute:

“Being able, even on a bad day, to walk on the beach and when you come back it’s not a bad day,” she says. “So those types of things are still good. I’ve had a really wonderful run, and I’m continuing to do more, much more.”

This feature was originally published in the February issue of ESSENCE Magazine.