This article originally appeared in the May/June 2021 of ESSENCE magazine, available on newsstands now.

Regina Goodwin, a fourth-generation resident of historic Greenwood, Oklahoma, still remembers the stories her grandparents told her about one of the most horrific incidents of racial violence in the United States. Incited by the claim that a Black man assaulted a white woman in an elevator, it’s said that a white mob threatened to lynch the suspect. When Black residents, some of them World War I veterans, showed up at the courthouse to protect the detained man, they found themselves face to face with the mob. Gun shots were fired as white vigilantes attacked the nearby African-American area of Greenwood over a period of two days, beginning on May 31, 1921. They looted and rioted, then burned Greenwood to the ground. Private planes were seen raining bombs down on buildings, with an estimated 1,500 homes and 600-plus businesses destroyed and approximately 10,000 people left homeless. “Black people were murdered and burned alive,” Goodwin says. “They were told to come out with their hands up—‘We won’t shoot.’ And they’d come out with their hands up and be murdered.”

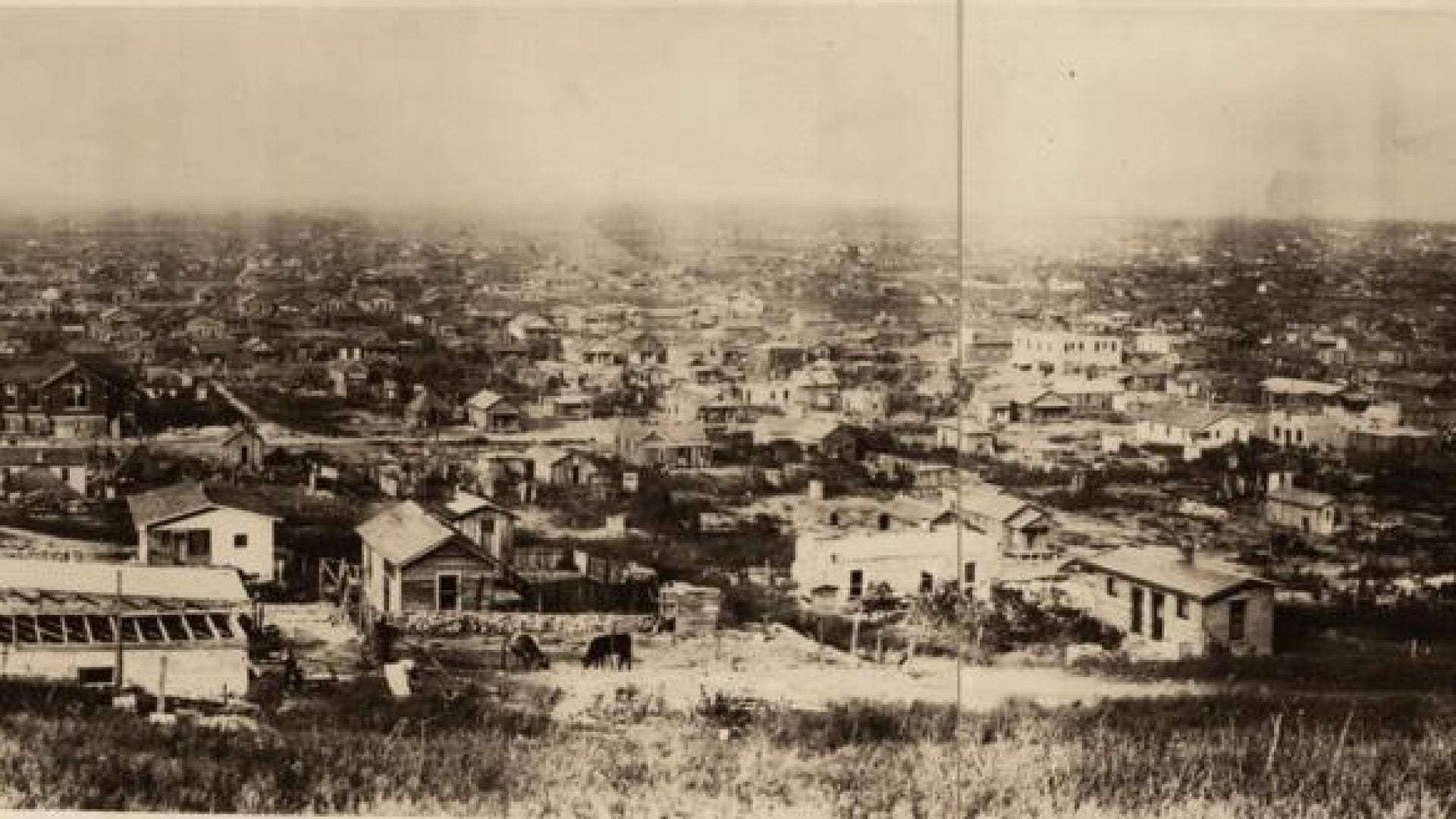

The exact toll of the massacre is still a bit sketchy, much like the faded and yellowed photos that attempt to document the events that took place 100 years ago. The estimate of how many people were killed, wounded and missing ranges from 300 to 3,000. Complicating matters is the belief that bodies dumped and not properly buried may still not have been found. “Eyewitnesses have identified where people are likely to be,” Goodwin says. “I sit on the committee that’s looking for mass graves. In two years, they haven’t looked where we asked them to.”

There are also differing accounts of what really happened between 17-year-old Susan Page and 19-year-old Dick Rowland in that elevator. But what is razor sharp, for those who count themselves among the survivors and family members of survivors, is the psychological anguish that remains. “The murderers were still walking around,” Goodwin says. “Nobody was ever charged. Nobody was ever convicted.”

Goodwin’s family first settled in Greenwood in 1914, when James Henri Goodwin moved his brood from -Mississippi. He wanted to ensure that his children would get schooling beyond the third-grade education they might have received otherwise. The 35 square blocks of Greenwood, which became known as Black Wall Street, were home to prosperous African-American–owned businesses and elegant residences with pianos and fine china. It was the self-sufficient community that O.W. Gurley had envisioned when he purchased 40 acres in 1905, determined to sell only to other Black people.

“Greenwood was a thriving community,” Goodwin says. “J.B. Stradford had a hotel to rival any of the finer white hotels. Andrew Smitherman ran the Tulsa Star newspaper. Simon Berry had what folks say may have been the first Black-owned airline charter service. These were the kinds of folks that lived in Tulsa.”

Stradford, a businessman who started out in St. Louis, was one of the early settlers. He’d already graduated from Oberlin College and received a law degree from Indiana Law School when he began building rental properties and opened a 54-room hotel. Another prominent business owner, Goodwin’s great-grandfather, James Henri, was the business manager of the Tulsa Star and cofounder of the Jackson Undertaking Company. A single dollar in Greenwood circulated 36 to 100 times before leaving the community a year or so later. This was why people referred to the area as Black Wall Street. Indeed, many argue that white jealousy was the real reason behind the massacre.

Seven years after his arrival, James Henri’s dream for his children was close to being realized: His son, Edward, was to graduate in June as part of the Booker T. Washington High School Class of 1921. Edward Goodwin, named most likely to succeed, was at the Stradford Hotel on May 31 when he got alarming news. “They were preparing for what we know as prom,” Goodwin recalls. “My grandfather was like any other senior celebrating getting through high school. And as they were decorating, word came that trouble was coming and they all needed to go home. They had no idea trouble meant the worst racist attack of domestic -terrorism in America.”

When the mob set the Goodwin residential and commercial properties on fire, death became a real possibility as Edward and his family hid inside their home. It would be the only property the Goodwins owned that wasn’t destroyed. “My great-grandfather had a very fair complexion and looked like a white man,” Goodwin says. “It was said that during the massacre, when the race mobs were coming down the street, he just waved them off, and they kept it moving.”

Those Blacks who weren’t arrested by the Oklahoma National Guard and detained in internment camps walked along the railroad tracks that divided the prosperous Black section of Tulsa from the area where some of the white people were struggling economically. Many Greenwood residents who ran for their lives ended up at the Tulsa Fairgrounds, where they were fed and given mattresses.

The Goodwins were among those who returned to rebuild—along with John and Loula Williams, owners of the Dreamland Theater. “Despite, all of our property that was burned to the ground, my family stayed,” Goodwin says with great pride. “That is the story folks need to know—that even though it was destroyed, Black folks rebuilt Greenwood to its same glory.” By 1942, approximately 242 Black-owned businesses had been re-established.

By the time Regina Goodwin was born, however, in the 1960s, there wasn’t much left of the rebuilt Greenwood. Even Booker T. Washington High, used as a triage center during the massacre, was renamed and converted into the elementary school that she would attend.

By the 1970s, a new threat displaced much of what was left of the community. “You had what folks called ‘urban renewal,’ which is ‘urban removal’ for many folks,” she says. Goodwin’s parents were among those asked to move out of their home. Almost 50 years later, she says, there is still an empty lot in the space where their house used to be: “You destroy the houses and you begin to see the demise of a community, Black communities in particular.”

But for Goodwin, the fight is not over. She decided to pursue a life in politics. As a state representative, she’s continuing to do the work she says she was already doing as a private citizen. “My grandmother told us that service is a rent you pay for room and board on earth,” she explains.

Greenwood was a thriving community. J.B. Stradford had a hotel to rival any of the finer white hotels. Andrew Smitherman ran the Tulsa Star newspaper. Simon Berry had what folks said was the first Black-owned airline charter service. These were the kinds of folks who lived in Tulsa.”

—Regina Goodwin, a fourth-generation resident of Greenwood

After the massacre, her great-grandmother Carlie Marie Goodwin filed a lawsuit demanding reparations. “Even knowing that the murderers were still walking around, she had enough tenacity to go down to the courthouse and file that suit,” Goodwin says. “And of course, she was rejected outright. Now, in 2021, I still firmly believe in reparations. Many folks were never made whole. We’ve got 106-year-old seniors who are survivors of the massacre. Why are their needs not being addressed?”

Today, there’s not much left of what Gurley imagined Greenwood could be.

The notion of rebuilding another Black Wall Street has been hampered by the 200-acre Oklahoma State University satellite campus and the Tulsa Drillers baseball stadium. “People hear glorious stories of Black Wall Street, so they expect to see a thriving Black community,” Goodwin says. “When you come now, you’re going to see gentrification and a lot of white folks in the area that was once a bustling Black Wall Street.” Black people at this point make up less than one fourth of the Greenwood Historical District’s residents. “It’s difficult to negotiate when you don’t own the land,” Goodwin notes. “So I’ve asked the mayor to give land back to the Greenwood Cultural Center, since they gave 200 acres to OSU Tulsa.”

It’s fair to say, most Black folks had never heard of the Tulsa massacre until they saw the first episode of HBO’s Watchmen and witnessed the businesses owned by beautiful Black people set on fire by armed white men in a heinous act of hatred. The heartbreaking scenes, from a fictional cable show set in 1921, were all too real. We also watched the gruesome killing of Black people in Tulsa on HBO’s sci-fi series Lovecraft Country. We had to catch a history lesson from a cable network, because what happened in Greenwood was conveniently omitted from our textbooks. But decisions to add it back to the Oklahoma public school curriculum were made last year. And while the rest of the country catches up on the tragic yet little-known storyline, Goodwin continues her family’s mission of speaking truth to power. She’s walking in the footsteps of her grandfather, who founded the Oklahoma Eagle newspaper in 1936 for that purpose; and of her father, Edward, Jr., who, with his two brothers, later took over the paper. “We owe it to our ancestors to never forget what happened, and to move forward and to be excellent,” Goodwin emphasizes. “I know that there are people here that care. We have resilient, intelligent and tenacious people here, both Black and white, that will fight for right.”

Until, the battle is won, Goodwin will continue to drive around with a personalized license plate that reminds us of the wrongs that have never been made right. Pay BWS, the tag reads, in other words, “Pay Black Wall Street.”

Lee Anna A. Jackson (@LeeAnnaAJackso1) is a New York-based writer and research editor.