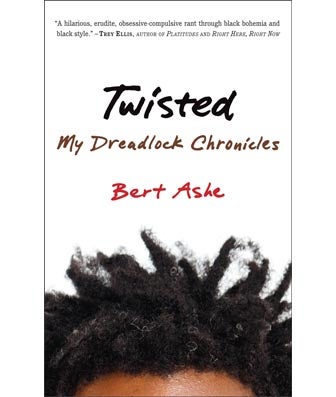

We talk about our hair journey on a regular basis, but what’s it like for a man? Twisted: My Dreadlock Chronicles is a unique memoir that explores Black hair from a man’s point of view. Infused with humor and self-reflection, Bert Ashe uses his own hair-locking experience (as a middle-aged college professor) not only to explain the history of dreadlocks, but also to unpack complicated issues of identity, politics and gender. Here, he delves into Black hair in contemporary America, and why he wasn’t surprised by Giuliana Rancic’s comments about Zendaya’s hair.

ESSENCE.com: A lot of women don’t like the term ‘dreadlocks.’ Tell me a little bit about your thought process with using the term “dread” in your title?

Bert Ashe: For me, the name of the hairstyle is dreadlock. I simply don’t have much acceptance or much agreement with people who focus on those five letters, D-R-E-A-D, and somehow suggest that that group of letters is somehow a negative aspect of the hairstyle. To me it’s not.

ESSENCE.com: What are the top three things you learned about Americans and how they perceive themselves through this journey of having locks?

Ashe: Even though the proliferation of dreadlocks has drastically skyrocketed, it’s still rather small when you think about it. But far more people are walking around with their dreadlocks as we speak, than ever before, and a far greater range of personality. I’ve seen grandmothers in dreadlocks. I’ve seen little children in dreadlocks. I’ve seen, and everywhere in between, and yet the fact that the hairstyle signals Jamaica seems to be stuck to it in ways that I wondered if it will ever stop. Also, Americans both love difference and hate difference at the same time. Let me give you an example. A twist out is so fascinating to look at that when African-American women are featured in commercials it’s not at all unusual to see them [wear it]. But let that same African-American woman sit for an interview at IBM or Xerox, they might have a little more difficulty.

ESSENCE.com: Are you saying, large companies believe twist outs are cute and playful, but not serious for work?

Ashe: That’s exactly right. There’s a strand in the book where I talked about the Golden Age of Dreadlocks, which I flipped from, say 1979 or so to the early 1990’s. The way that Americans feels with something that is scary and unusual and confrontational is by laughing at it, reducing it, and controlling it. Therefore it becomes barter for humor, but at the same time America doesn’t really take it seriously in any sort of way.

ESSENCE.com: Many women are upset with other women who get faux locks. They think believe the look ‘cheats them from their journey.’ What are your thoughts on that?

Ashe: To a certain extent I agree, although I’m not upset with them, because people, certainly a lot of white people and there’s certain number of black people as well, are probably are unaware of the fact that the locks aren’t ordinary, grown from the locking process dreadlocks. But, it’s their choice to do it. But what’s signified by dreadlocks on some fundamental level, it’s still there even though the individual didn’t go through the locking process themselves.

ESSENCE.com: What are your thoughts on the Zendaya controversy

Ashe: I certainly wasn’t surprised by Giuliana Rancic’s sort of polite and seemingly, ‘Oh, nothing will happen to me if I say this ridiculous thing.’ [The show is meant to] to say chatty, snarky things about what people are wearing. If they weren’t chatty and snarky she doesn’t have a show. But, the fact that she was perfectly comfortable saying what she said says to me, says A. She didn’t expect any blowbacks and B. That on some level she was speaking for a kind of larger American populace that feels the same way that she does, and that she would get some mileage out of it.

ESSENCE.com: As a man, how do you deal with people wanting to touch your hair?

Ashe: People don’t ask to touch my hair and people don’t touch my hair. I think that because I’m a 56-year old man that the sort of automatic presumed access to the black female body isn’t there. I do a lot of reading and I know that the exasperated black female, says A. “I wish people would stop asking.” B. “I wish people would stop touching it without permission.” But it is absolutely fascinating to me how little that has happened to me.

ESSENCE.com: What do you want people to walk away with after reading your book?

Ashe: Whenever I post an article about my book or an excerpt about my book, people say I’m over intellectualizing the total idea of hair and that ‘It’s just hair!’ But after reading my book, I want them to understand there’s more going on in terms of the cultural realities of hair in America and the world more generally. I would also love for men to read the book and start asking themselves questions. ‘Why am I’m wearing a baldie? What’s the difference between a quarter inch, really sharp short cut and then going bald? Why am I choosing this hairstyle? What does this hairstyle mean in terms of my movement through the public sphere?’