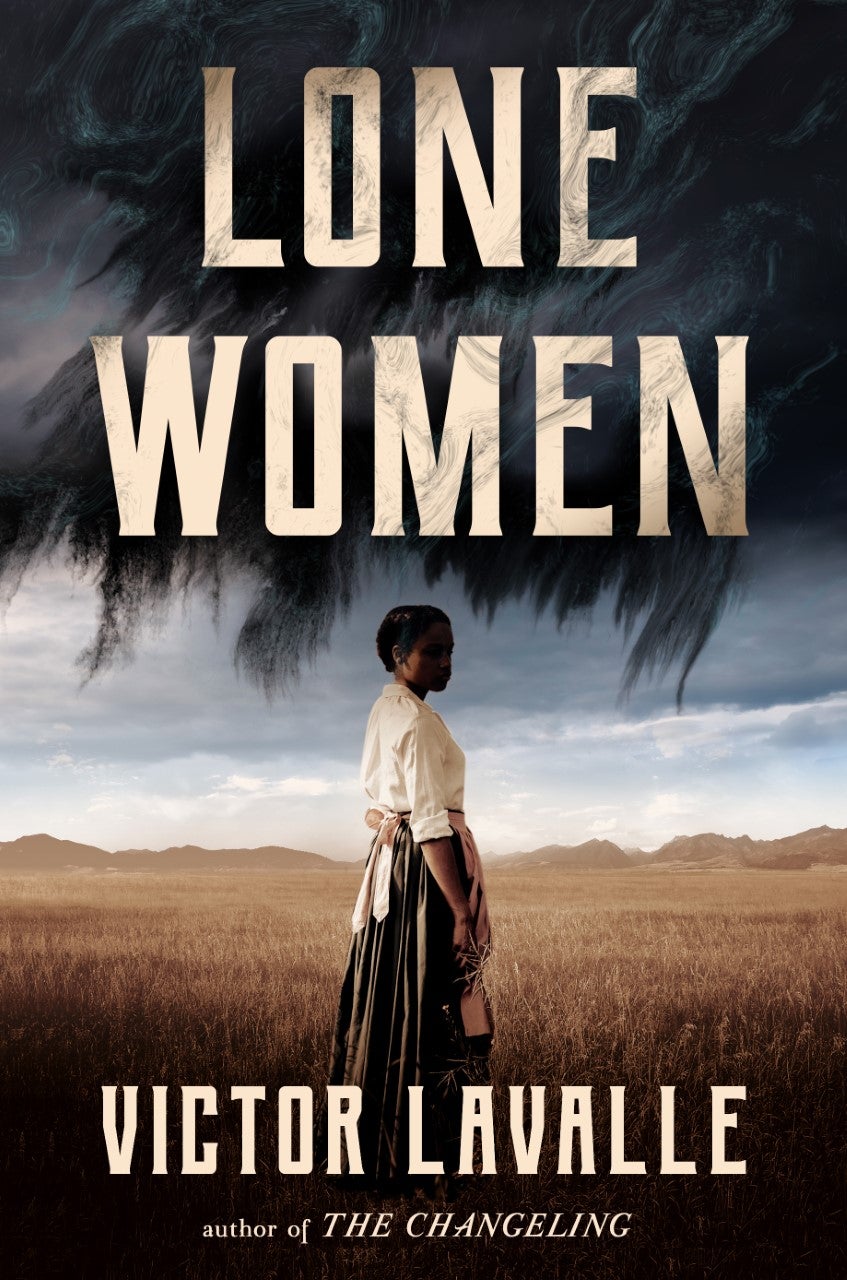

In his new book, Lone Women ($27, One World), author Victor LaValle transports readers to the desolate plains of 1915 Montana where Adelaide Henry tries to outrun a secret that would rather not be contained. LaValle describes his writing as “taking the real world and putting it through a very weird blender, adding in fantastical things so you can understand it better.” It’s an apt description—though it’s set more than a century ago, this eerie story of a haunted would-be homesteader cobbling together a life she doesn’t want to escape from feels both prescient and modern. Here, we talk to LaValle about casting off curses, crafting complicated monsters and the beauty of interdependence.

Where did the idea for this book come from?

I was in a bookstore at the University of Montana and I found a book called Montana Women Homesteaders: A Field of One’s Own. I’d never heard of women homesteaders who came to the territories totally alone. What made me say, “I want to write about this,” was the first time the author mentioned a Black woman who owned land and had a home that is now a historical landmark. It became more interesting when I also saw there was a Chinese population and Japanese folks out there making homes. Then, of course, there was the Native population who had long been there. The more complicated the picture became, the more I said, “Maybe I could tell this story.”

We’ve recently seen some major setbacks to women’s autonomy. Why was it important for you to write about these exceptionally independent women right now?

The funny thing is, the first version of this book was a story from 2014, and it felt vital and important then. But when I came back to it in 2018 to expand it into a novel, it was a different context, a different time. All but one of the things the women in the book experience are based on historical fact, and the more I added those things, the more it sounded like today. It’s a cliché, but the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Most of your novels feature male main characters. What challenges did you face in writing from Adelaide’s point of view? Were there things that felt surprisingly easy?

The biggest thing was to live in a different body. I’m not a tough guy or a big guy, but I rarely feel scared or on guard when I enter a space. I wrote something like, “She’s going to go into town and she’s going to go to this show and then, it’s going to be hard, but she’s going to walk all the way back to her claim.” And my wife was like, “Wait, what do you mean she’s walking back to her claim in the middle of the night alone?” So that was a real adjustment. But on the other side, I got to live in the beauty and joy of the friendships my wife, mother and sister have. I don’t have that circle, that level of comfort and love that women have. Some of my favorite stuff was when the women started bonding. I loved writing that.

Your books, including this one, often feature the monsters that ain’t—and people who are. What draws you to these characters?

First, I love monsters. I grew up on horror, and often, when I’m reading a novel or watching a movie, I look at who the good person is supposed to be and I look at who the monster’s supposed to be, and there’s a part of me that identifies more with the monster. I’ve been made the monster often: I shouldn’t be at this school. I shouldn’t be in this neighborhood. I shouldn’t be on this airplane. In a fair bit of horror, it’s far too easy for me to be the thing causing fear, especially since it’s usually a white woman who’s in danger. So as I’m writing a cool monster, often halfway through I go, “What’s the monster’s point of view? Is it really a monster?” And many times I go, “I think it’s not. I think maybe the real monster is the people dealing with it.” That feels closer to life as I understand it.

Weather, bandits and racism kick your characters’ tails in this book. What would be your biggest stumbling block if you were a homesteader in Big Sandy?

I can’t even start a fire, so that’s number one. But more than that, I’m antisocial and this world required people to look out for each other—even people who hated each other. I feel like most people would be like, “Just let him die! Let him freeze, it doesn’t matter.”

Many characters in Lone Women have a curse they must deal with before they can create the life that they want. What have you had to reconcile to put you on your chosen path?

I was raised by my mom and my grandmother, and my dad started a new family and had nothing to do with me. When I was younger, I thought his rejection meant I was worthless, and I spent a long time refusing good things coming my way because I felt I didn’t deserve them. I was going to a therapist in my 30s and I told her how he abandoned me and treated me like garbage, and she said: “You know that’s not his story of what happened. You can’t continue to tell yourself that you’re a bag of garbage he’s someday going to pick up, because he doesn’t even know that there’s a bag of garbage waiting for him. You need to start telling yourself a different story about what you are.” That was the beginning of me saying, “The story I’d like to tell is I’m kind of a miracle like everyone is, but specifically like every kid who gets abandoned. It’s a miracle that I made it through all these things and I’m writing books and doing the things I want to do.” When she got me to tell a different story, I was able to accept the things that came to me.

What do you hope readers do when they finish Lone Women?

I hope they cheer! And I would love it if they dove into the history of Montana or wherever they’re from. There has been a concerted effort to erase true history to protect one group’s feelings, which is wild, but it’s not new. I feel like the antidote to that is people doing their own reading.