Nykia Watkins was 15-years-old when she was sentenced to two years in prison at the Juvenile Correctional Complex in Topeka, Kansas. “Being incarcerated was so traumatic. I was one of those kids who sat in jail and had staff point fingers in my face…I’ve been one of those kids that [was] strip searched. Those kinds of things are dehumanizing,” she said.

Once she was released, Watkins says just meeting the needs of day-to-day life was difficult due to a lack of support resources like counseling, adequate housing, transportation, and food.

“Those things you experience make you never want to set foot back in jail. But somehow because of the way the system is created, you do set foot back in jail,” she told ESSENCE, calling America’s juvenile justice system a “rotation of unsuccess” that’s in need of reform.

Watkins’ experience is all too common in the United States, where an estimated 1,909 children are arrested daily. The number of incarcerated children has declined over the past decade due to some changes in policy and practice. However, America’s children continue to be criminalized at high rates and disparities have persisted. Youth of color especially are disproportionately impacted. In every state, Black youth are more likely to be incarcerated than their white peers and about five times as likely to be incarcerated nationwide.

“It’s not because young people of color commit more crime than white youth,” said Liz Ryan, President and CEO of the Youth First Initiative, a national campaign to end youth incarceration. “The justice system treats youth of color much more harshly and much more punitively than white youth, even when they’re charged with the same offense,” she added.

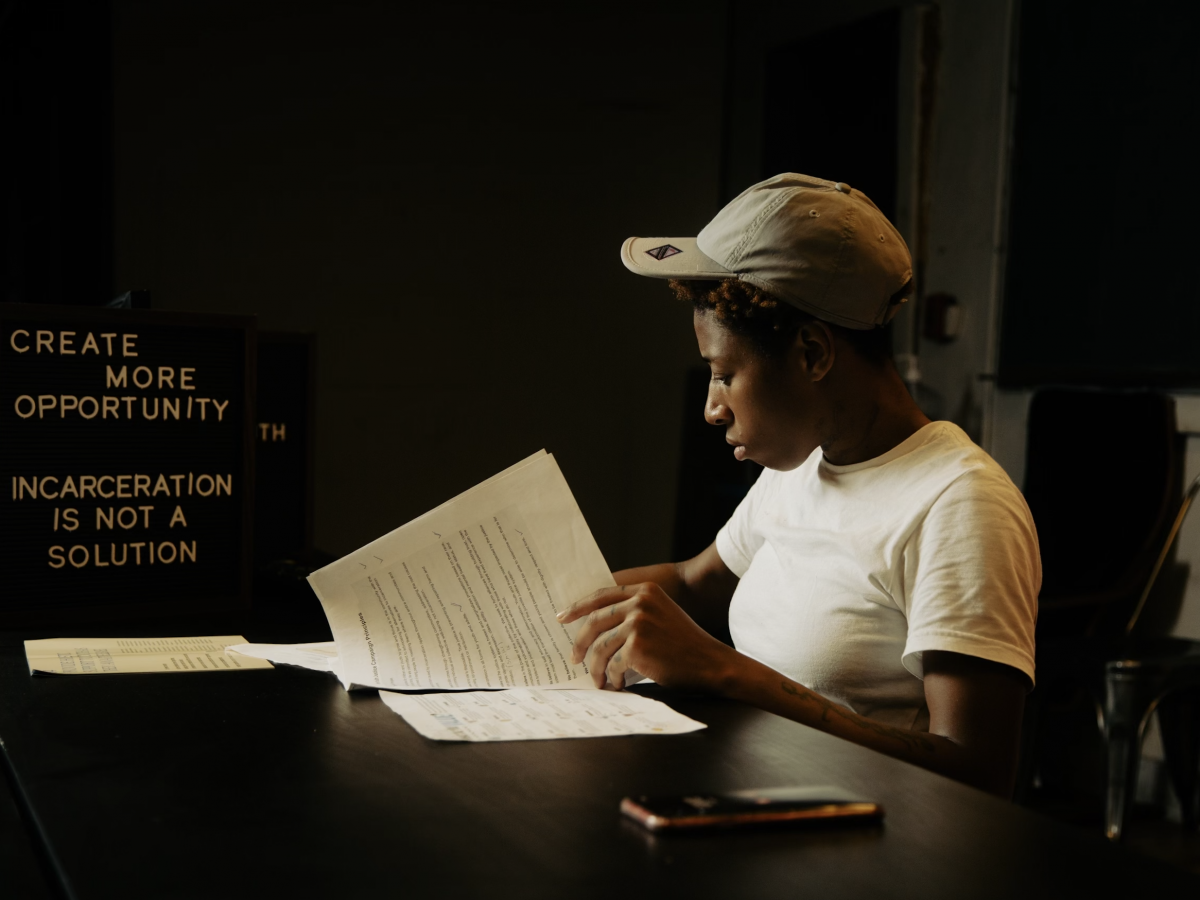

Nykia Watkins

“Yes, some kids make mistakes in life but we are not our mistakes. They do not define us,” Watkins explained. Now a youth leader at Progeny, an organization working to end youth incarceration in Kansas, she is passionate about sharing her story and advocating for community-based alternatives to prison both locally and nationally.

“We empower other youth by our stories. We show them they can be in different spaces and become leaders, policymakers and just make a difference in the community,” she said.

As awareness of the racial disparities that exist in America’s juvenile justice system increases and national attention on police violence against children grows, Watkins believes reform of the system has to be a collective effort. She is just one of the many youth leaders working in states across the country to end the practice of youth incarceration.

“Incarceration shouldn’t be the go-to, it isn’t the solution. Support is, you know, being heard and finding different options. Those are solutions,” said Briannah Stoves, a youth leader with the Care, Not Control coalition in Pennsylvania.

President Joe Biden promised to prioritize reform of America’s juvenile justice system in his 2020 campaign. Biden’s plans include eliminating racial disparities in prison, implementing community-based alternatives to prison, ensuring fairer sentences, and implementing policies based on input from children and young adults who interacted with the criminal justice system as children. These young advocates say they want to see those promises of reform upheld by the Administration with meaningful input from people who have been personally impacted by it.

Stoves uses poetry to express how being incarcerated at the age of 14 impacted her life. Sharing her experience and advocating for policy reforms that could change outcomes for others is why she became a youth leader with the coalition and the Juvenile Law Center.

Now 18-years-old and working toward becoming a welder, Stoves says she really values her role as a youth leader because she’s able to have a positive impact and she feels seen beyond stereotypes.

“You are the writer of your own story, but once you’re incarcerated, that pen gets taken away from you…once you get that pen back you have a label. It shouldn’t be that way and I want everyone to see that and understand that,” she told ESSENCE.

These young women say that their efforts are not only centered on ending youth incarceration, but on working to shift resources away from it and towards things that young people want and need to thrive and lead productive lives.

“Not many people are focused on preventing young people from getting there [incarcerated], or finding out why a young person is there actually, and creating programs that are centered around healing that young person. That really motivated me to just want to speak up about the issues even more,” said Jazmine Rogers who has worked as a youth leader with Progeny for the past year.

Though Rogers has not been incarcerated herself, the nineteen-year-old shared that seeing the negative impact incarceration has had on her family and friends is what inspired her advocacy work. As youth leaders, both Rogers and Watkins help create campaigns and present before a legislative committee in support of policy reforms. They also facilitate youth visioning sessions asking their peers to share their ideas, including how they would redirect the estimated $113,000 cost per child spent to incarcerate them in Kansas and invest in their communities.

Jazmine Rogers

“I want people to learn to listen to young people more when they speak out, listen to them more if they’re telling you that they need help or if they want to do something because they’re the masters of their own experience, ” Rogers said. “They are more than just their incarceration. They have their own dreams and hopes and goals after they’ve been incarcerated. Give them an opportunity to reach them.”