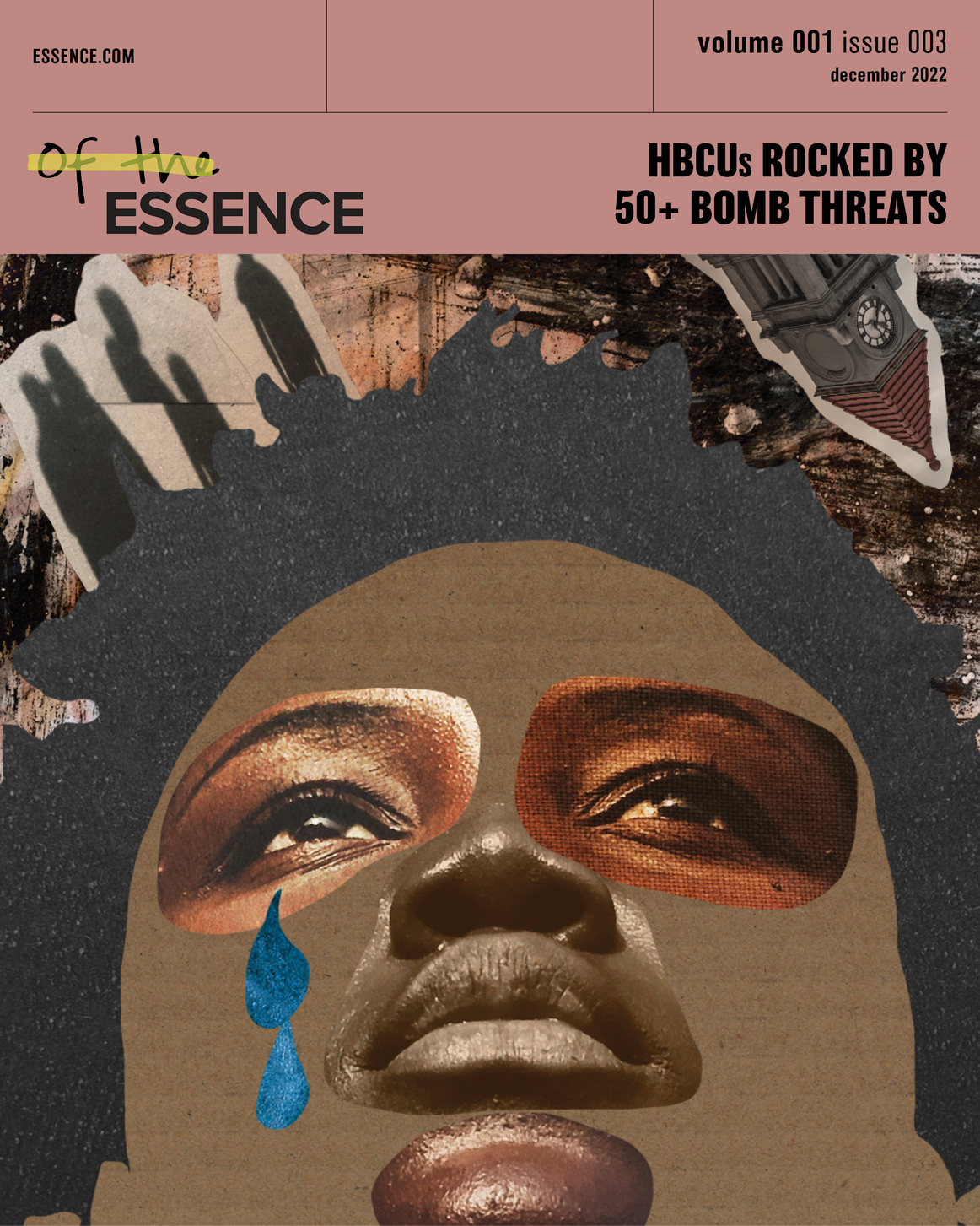

There Were Over 50 HBCU Bomb Threats In 2022. Students And Faculty Are Opening Up About Their Experiences.

The selling point of attending an HBCU is the opportunity for Black academics to learn and live in community with one another. Some students even refer to the HBCU campus environment as a “bubble”—an insulated refuge from an overwhelmingly white world. While those bubbles are centers of Black communion where students can thrive alongside others like themselves, they are still permeable.

Since the beginning of this year’s Black history month, bomb threats have been made against a number of HBCUs, puncturing these safe spaces and terrorizing those who sought a safe haven. Between January 4 and February 16, 57 institutions, including historically Black schools, houses of worship, and other faith-based and academic centers, were targeted with threats of violence. An FBI press release notes that no explosive devices were found. A September update from the bureau describes the investigation as ongoing. The FBI says the events are being examined as “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremism and hate crimes.”

On November 14, the bureau released another update, announcing they had identified a single juvenile believed to be responsible for the majority of the threats. Because of the individual’s age there is limited information made public about them, but the release notes that the Department of Justice is working with state prosecutors to hold them accountable. The update also notes that a distinct set of additional threats primarily targeting HBCUs, from between February 8 and March 2 of this year affecting at least 19 institutions, appears to have originated overseas. A separate set of bomb and/or active shooter threats was said to have originated overseas as well and was described as “ongoing,” beginning June 7 and affecting over 100 high schools, several junior high schools, and 250 colleges, seven of which are HBCUs.

Following the events, Howard University, which USA Today reported as having received the most threats of all the schools, extended resources to students such as a mental health day and town hall meetings. Still, for students like senior Eshe Ukweli, processing the threats has been complex; a mix between anger and desensitization. She says that being targeted sometimes feels like the price of admission.

“Coming to Howard University, there’s this [notion] that you’re coming home to your community, to the Mecca,” she tells ESSENCE. Ukweli is a transfer student who sought safety in Howard after having experienced racial harassment at her predominantly white institution (PWI) previously. She’s adamant that the numerous security threats haven’t broken her down. At the same time, she notes that they do have an effect on students, as well as the capability to tarnish the school’s image. “I just feel definitely desensitized and maybe a little hint of anger because it’s something that contributes to this larger identity [that] HBCUs are not the place to be,” she says.

Ukweli understands targeted threats of this nature, in the context of American history, as attempts to cause fear and terrorize Black communities. She draws from a wellspring of strength in the face of such violence that runs decades deep. “We came here with a passion,” she says. “We came here to contribute to Black excellence and to have this community, to have access to one another. So we’re not going to be stopped; we’re not going to be broken by people who want to intimidate us.”

Her sentiment is echoed by Howard University executive director of public safety and chief of police, Marcus Lyles. In a statement shared with ESSENCE, Lyles references the fortitude of the Howard community.

“Our students, parents, employees, alumni, and neighbors know that Howard will never stop living out its institutional mission and that every effort to thwart our work only emboldens us to positively impact more lives,” Lyles says. In his statement, he also expresses gratitude for the school’s Department of Public Safety, the Metropolitan Police Department, the FBI, Homeland Security and U.S. Capitol Police for their support throughout the situation. “We want to know that we aren’t in this alone. We want to see the government of the people invest in the technology, personnel, training, and facility upgrades that are befitting of Howard’s mission to do good for all people within and beyond our borders.”

Despite not having located any explosives related to these incidents, the notion of an “empty threat” does not apply here. As Lance Wheeler, director of exhibitions at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta said to the Associated Press earlier this year, these bomb threats are part of a larger history of violence against Black edifices that have resulted in tragedy: “people of color don’t have that privilege to think it’s not real.”

The documented historical record of bombings to Black institutions and edifices are the context in which these HBCU campus communities, well-versed in their own not-too-distant history, understand the present-day threats. Among the most notorious is the September 1963 bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The attack on the church, known as the core of the city’s African American community, happened the same year that Birmingham agreed to desegregate lunch counters, restrooms, and drinking fountains — to the ire of white segregationists. Four Black children, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley, were murdered.

The city was so frequently a site of racist violence that it was dubbed “Bombingham” during the Civil Rights Movement. A consistent use of dynamite led to the Smithfield neighborhood’s nickname “Dynamite Hill.” The home of activist Fred Shuttlesworth, a reverend who fought to desegregate buses, was bombed on Christmas Day 1956 — a week after bus segregation in Montgomery was ruled illegal and the bus boycott drew to a close. Reverend Shuttlesworth survived the attack and was undeterred in his convictions to continue his work with the movement. He died in 2011.

Decades later and hundreds of miles north, 61 residential homes in a largely Black neighborhood were destroyed by the Philadelphia Police Department in what is now known as the MOVE bombing. The Black liberation group MOVE had become a target after growing discord between the organization and the police department. On May 13, 1985, 11 people, including MOVE’s founder, were killed after a police helicopter dropped a bomb on the site of the MOVE house and allowed the resulting inferno to burn. Five of those killed were children. It would be decades later, in 2020, before the Philadelphia City Council issued a formal apology. Though the initiative stands as an effort to acknowledge the racist terrorism wrought over 35 years ago, such anti-Black massacres are in no way a thing of the past: nine African American parishioners were murdered at Mother Emmanuel AME, one of the oldest Black churches in the nation, by then-21-year-old white supremacist Dylann Roof in 2015.

HBCU students have been kept safe physically with respect to the bomb threats of this year, but there is a strategic damage done to these communities as they go through the motions of lockdowns and evacuations. North Carolina Central University (NCCU) was among the schools forced to take action after receiving bomb threats in January, as well as this past fall semester. NCCU counseling center director Charnequa Kennedy says that regardless of whatever other stressors may have factored in, the outreach of help-seeking increased in the wake of the incidents.

“Physical health is not separate from what happens mentally and psychologically,” Kennedy explains. “Those things occur together, in terms of a mind-body connection. And for our students, for those who report having experienced some level of discrimination, we see a higher prevalence of things related to depression, overall stress, including academic distress. The psychological distress overall for students looks different when there has been a concern that impacts their safety. That includes their physical and psychological safety.”

Norfolk State University was another one of the schools that received bomb threats in January. The institution’s counseling center director Cheniqua Goode notes that they, like NCCU, have seen an increase in students seeking mental health services but can’t trace the rising numbers all directly to the security threats. Goode understands them as another added layer to the myriad other stressors students must process, including the pandemic and the general difficulties of being in university.

“Having to deal with academics, adjustments to college life, being away from home and the stressors that just come with college, but then to add on a threat to your safety, that can increase anxiety for a lot of our students, even some depression,” Goode says. “Because the anxiety is [around], ‘Ok, what’s next, what’s next, what could possibly be a real threat that plays out?’” She points to an encouraging cultural shift in attitudes about mental health reducing stigma surrounding seeking help and characterizes NSU’s students as particularly resilient. Despite the students’ determination to press on in the face of such threats, Goode recognizes the incidents’ potential to diminish what the campus community may consider to be a safe space. “[When] it’s been in the news that the HBCUs are the ones that are being targeted, students are [left thinking], ‘Ok, because of my color or because the university that I attend, am I no longer safe at a place I went to for comfort, for safety, for inclusion? In a place where I’m supposed to be comfortable where I am around people who are like me?”

NCCU junior Cameron Emery, who is vice president of the university’s Student Government Association, was upset to see the spate of threats leveled against so many in the HBCU community this year. “To see it go over across my entire HBCU family was a little disheartening because it seems as though we can’t lose to win,” he says. “We come here to find ourselves and get our education and be successful and for anyone to act or incite violence just because we’re trying to succeed is disgraceful.” Emery’s concern about being among the schools threatened is tempered by the faith he has in NCCU’s security. “The situation of course was not a pleasant one, but because our university on both occasions had great protocol it seemed as though it was easy to navigate through.”

NCCU police chief and director of public safety Damon Williams says that both the January and August threats to the school are currently being investigated, with no arrests yet made. While the August threat was more localized and resulted in an evacuation of the nursing building specifically, the January threat called for a larger scale response.

“In January I called for a full evacuation of campus, so we used every mechanism that we had to lock the campus down and put out messages to the students,” Williams says, noting the school is outfitted with systems that light all computer screens up with a system alert, a digital notification system which goes out to students’ phones, as well as an audible siren system. Williams says the current security protocols will be further strengthened by resources provided by both the federal and state government.

He says a $213,500 grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Education has already been allocated and will be fully utilized to support the counseling center, while a grant in excess of $800,000 provided through the UNC system will be used to make “significant security improvements on campus” — Williams references planned initiatives such as bomb detection animals, license plate recognition technology, and a drone that the security team hopes will aid in future investigatory processes and mitigate these occurrences going forward. Other HBCUs were also granted federal funds from the Nonprofit Security Grant Program as well as the Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention Grant Program, including Alcorn State University, Tougaloo College, Bennett College, Southern University and A&M College.

Like Ukweli, Howard senior Jayda Peets remains steadfast in her belief that her experience attending the school outweighs the emotional unrest caused by threats of targeted violence. Naturally, it is a trade-off she wishes she didn’t have to make. Both Peets and Ukweli reference feelings of desensitization; Peets thinks the university administration could stand to make a stronger effort to communicate and connect with the students following such harrowing incidents. “There’s just so much miscommunication and crazy events that go on at Howard every year that this sometimes just feels like just another one of them,” she says, noting that the university’s high-profile alumni — Phylicia Rashad, Taraji P. Henson, and the late Chadwick Boseman, to name just a few — as pillars that do a great deal of work upholding its reputation publicly, while frustrations about safety on campus don’t always match that image of the institution. Peets names recent protests to raise awareness about mold and rodents in student housing as issues alongside the threats that can be discouraging.

“Even the alum will tell you that communication is really lacking,” she says. “There’s always something going on at Howard. … We’re willing to compromise for that amazing experience of being around Black students who want to make changes in the world. Our school isn’t perfect on an administration level, but the students themselves really make up for it.” Peets says using humor to help process their feelings has been a common response for students in working through the events. “Talking to other students, the best way we could cope with it was through jokes. I feel like that’s a really big part of the Black community in general, coping with traumatizing events or just disappointing events through comedy to keep our spirits [up]. This was one of those things where it was on Twitter being made fun of, even though we all registered that it was a serious issue. What else can we do about it at this point?”

To be put in danger for the very same reason she’s attending the school in the first place hurts. But Peets’ network instills a sense of power and pride that can’t be diminished. “I’m used to being misunderstood by my peers and experiencing macro- and microaggressions from the people around me. A lot of students I’ve met at Howard have a similar story — that was why I came here, to get away from that and just find my bubble,” she says. What that HBCU “bubble” offers within, regardless of the threats lobbed from the outside, is enough to sustain her. “It is worth it to come to this school because you will be met with, even during these trying times, such a positive and uplifting community of Black students who also just want to be in an environment that is accepting, and to be accepted by the world.”

The students and faculty consulted for this story all shared the same resilient outlook. They acknowledged that these incidents are disheartening, but they refuse to be menaced out of their academic pursuits.

What is it about the communion of Black people finding themselves, finding joy, and ascending the ranks of an American educational system that inspires these faceless suspects to perpetrate such violence? Certainly their intent is to intimidate these campus communities, but it would appear that they’re the ones who feel threatened; by Black scholarship and the Black success stories that these institutions produce. But we shall not be moved.

**

Illustration: Jessica Willis @swaggerless

Writer: Charlotte Collins @19ccollins

Editor: Brooklyn White @brooklynrwhite

Art Direction: Sophia Little @so.lit