Michelle Obama’s Guiding Light

Michelle Obama was writing her debut memoir, “Becoming,” and thought, what on Earth am I doing?

It’s hard to imagine the beloved First Lady ever being unsure of herself, but that doubt resurfaced as she prepared for her latest title, “The Light We Carry: Overcoming In Uncertain Times.” Her internal monologue was laced with fear: “What are you doing? You could just be at home, comfortable, not saying anything.” It was a week before the book’s publication date when we spoke, and she still didn’t feel at ease about the endeavor.

A lot has changed since Mrs. Obama published her autobiographical best-seller in late 2018. About a year after its release, the entire world would be shaken by a pandemic. “The Light We Carry” speaks to the uncertainty that has followed since; yet the assurance in her voice makes you feel like anything can be overcome.

“I always had this flame inside of me. I knew it when I was little. I don’t think I’m unusual in that sense. I think a lot of kids, particularly kids of color, we know what we’re capable of. We’re born into this world with a flame,” she shares.

In her new book, which was released on Nov. 15, she recalls a time she overcame at a young age. At about four years old, Mrs. Obama was selected to perform in a holiday recital. During the rehearsal she noticed an oversized, plush turtle perched next to the spot where she was supposed to perform. Despite her pounding heart, she approached the stage and found that the turtle wasn’t as big and intimidating as she thought.

The turtle comes to symbolize fear of the unknown, even in our adult lives. I asked about the other “turtles” in her life. “This book,” she shares with me over the phone. “But that comes any time anyone is about to release their words into the world.”

“The Light We Carry,” like our conversation, vacillates between the personal and the interpersonal, with Mrs. Obama organically considering the broader implications of her ideas. “Over the course of our lives that flame is either fueled by love, acceptance, and opportunity, or it’s slowly stomped out by racism or feelings of ‘not-enoughness,’ she says. “A flame burns internally and it’s there,” she observes, “but what comes from it—the light—is a thing that we can share. And there’s power in not just knowing and fueling the flame, but in creating something that emanates beyond us.”

Sharing light in a world of chaos and uncertainty is not easy. Many of us are just trying to stay afloat navigating our own paths. For some women, especially those who are Black and working class, they’re more likely to feel like they are drowning.

At a time when Black women’s labor was heralded as essential work in the height of the coronavirus pandemic, many didn’t, and still don’t, get essential pay. I ask her about this delicately, hinting at her own class privilege. There are women, myself included, who can afford to be still and ponder life’s lessons from a former First Lady; others are working multiple jobs just to keep their family fed.

We as women have got to prioritize. We cannot wait for everything to be fixed and working perfectly for us to take the time that we need to tend to our mental health.

Michelle Obama

“It’s easier said than done when you are overwhelmed, when you feel invisible, when you live in a world that is not cut out for you,” she acknowledges. “But what we do know is that we have to step out of that chaos for a moment, whether it’s a moment of quiet after you put the kids to bed, it’s at church in the pew, it’s on the walk you take to and from your job. We as women have got to prioritize. We cannot wait for everything to be fixed and working perfectly for us to take the time that we need to tend to our mental health.”

Mrs. Obama then steps back, noting how Black women in general take on other people’s burdens. “We don’t say no, right? We are taking care of our kids. Oftentimes we are supporting our own household doing it on our own. We’re taking care of aging parents, and going to school, and taking a call from cousin so and so who needs X, Y, or Z,” she states. “We’ve got to start carving out time for help. It’s part of getting ourselves out of other people’s mirrors and unburdening ourselves.”

As one of the world’s most high-profile figures, Mrs. Obama had to prioritize quiet moments in the earliest months of the pandemic. Despite her public work driving voter registration and supporting good causes, she started to feel cynicism creep in. “Privately, I was finding it harder to access my own hope or to feel like I could make an actual difference…I’d never contended with anything like depression before, but this felt like a low-grade form of it,” she confides in her book.

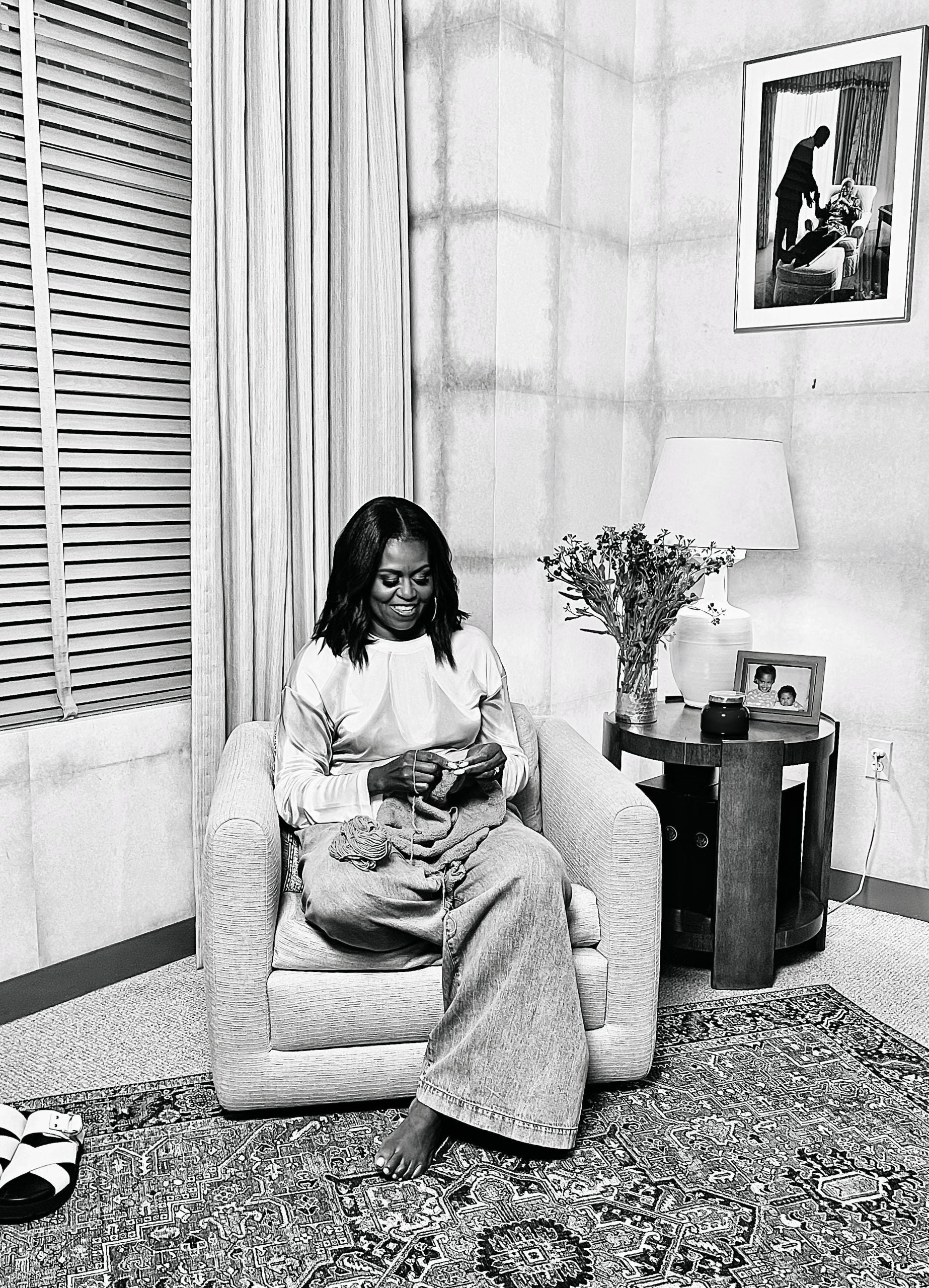

To help herself cope, she picked up two beginner-sized knitting needles and “unrolled a small bit of thick gray yarn,” she shares in the book’s first chapter. This is a metaphor, she tells me, for how we should take care of ourselves. “Put yourself into your own lap and tend to yourself. We’ve got to begin to have those conversations, because if we don’t prioritize it, then we don’t figure out how to do it at any income level, at any level of struggle. We don’t do it when we do have resources and time. So we have to talk differently about where our priorities lie, and we have to start putting ourselves higher on the priority list.”

Well before she had to contend with the demands of being a public figure, Mrs. Obama had to contemplate whether she wanted to be in the spotlight at all. When her husband approached her about running for President of the United States, “that was probably the most terrifying proposition I ever had in my life,” she shares with me.

In our conversation, she reiterates her thoughts in “The Light We Carry.” “I talked about what I learned over time, watching my ancestors, my grandparents, my parents who were sometimes struck by fear. They were paralyzed by their fear. Their fear was justified,” she states. “Growing up in segregated Jim Crow America, people had every reason to be afraid of stepping outside of what they knew. [But] I didn’t want to be that person. My parents didn’t raise me to be that person. And I didn’t want to mirror that for my girls [daughters Sasha and Malia]. So I had to decode my fear, figure out with this run for the presidency, because we have the tools to get through it.”

Fear is powerful in that it can keep us safe, but it can keep us stuck. If we don’t learn how to decode when fear is saving us and when it’s holding us back, then we lose out on what opportunities and possibilities lie on the other side of that fear.

Michelle Obama

“I use my own story in my struggle with fear to help people understand that part of overcoming fear is practicing through it,” she says. “I quote Lin Manuel Miranda, a gifted artist who talks about dealing with his own fear: you have to turn that fear into rocket fuel, you have to let it push you. And that, you know, it’s as simple as practice.”

While she doesn’t hesitate to share her vulnerability, she doesn’t linger in it. “Fear is powerful in that it can keep us safe, but it can keep us stuck. If we don’t learn how to decode when fear is saving us and when it’s holding us back, then we lose out on what opportunities and possibilities lie on the other side of that fear.”

Mrs. Obama’s affirmations can also serve as lessons for how we relate to others in our daily lives. As we talked, the elephant in the room was, well, a GOP elephant. We spoke on Election Day, when predictions of a Republican “red wave” had captured the nation’s attention. Stoking fears about other people and highlighting differences were key parts of their mostly failed strategy.

Though neither of us say it explicitly, “The Light We Carry” serves as a torch out of those dark, ugly politics. Through anecdotes in each chapter of the book, Mrs. Obama shares the tools she—and others within her trusted orbit—uses to see the light at the other end of our challenges and embrace what may be different.

“This is a good time for us to all put our tools on the table and start figuring out how do we cope in these times, because they’re not changing anytime fast,” she shares. “We don’t have the right or the bandwidth to quit. So we have to figure out how we are going to sustain ourselves and each other. We’ve got to develop the resilience of our parents and our grandparents, now more than ever. But we can do it together.”