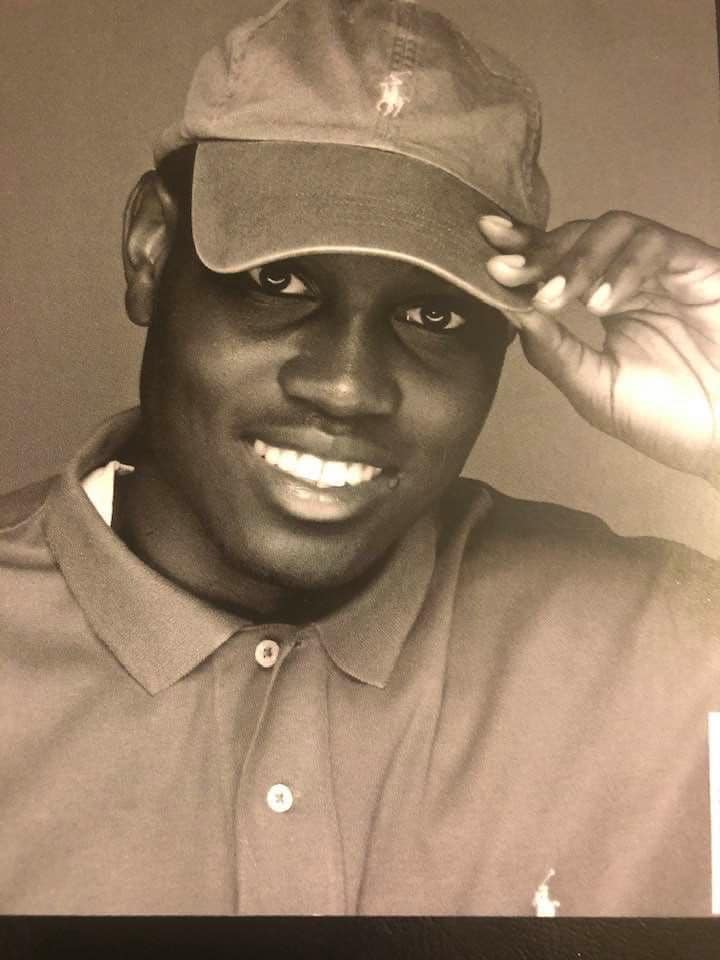

The death of an African-American jogger at the hands of two armed white men on the streets of a quiet Georgia neighborhood reminds us, once again, that race in America is a matter of life and death—and that justice is rarely granted equally. Yet buried in this tragic and outrageous story is an opportunity for us to change our criminal justice system. The death of Ahmaud Arbery—and what has and has not happened since he died—illustrates the singular importance of an elected position most of us rarely think about: prosecutors.

Elected prosecutors hold tremendous authority, discretion, and power to shape the lives of entire communities. Most states elect their prosecutors, usually called district attorneys; and there are roughly 2,400 elected prosecutors nationwide. Yet many of us couldn’t name our local prosecutor, and even politically engaged Americans often pay little attention to local elections like those for DAs. But in cases like those surrounding Ahmaud Arbery’s death, we can see just how important they are.

When Arbery was shot and killed on February 23 by Travis and Gregory McMichael, who had armed themselves and chased Arbery in their truck, no arrests were made and no charges brought against the McMichaels. The case lay dormant for two months, during which three different district attorneys failed to pursue charges against the McMichaels.

The first prosecutor to handle the investigation into Arbery’s death recused herself from the case after four days, citing her connection with one of the suspects, who had been an investigator in her office. The investigation was taken over by a DA from another district, who filed no charges and advised the police that the McMichaels had acted legally. He falsely described Arbery as a “criminal suspect” and referred to his “apparent aggressive nature.” He later recused himself, under pressure from Arbery’s family, because his son had worked with Gregory McMichael. The investigation was again reassigned, and the third prosecutor declined to pursue charges until May 5—the same day that a graphic cell phone video of the encounter between Arbery and the McMichaels emerged. Finally, on May 7, the McMichaels were arrested.

What do all three DAs have in common? They are white—like 95% of elected prosecutors nationwide, as the Reflective Democracy Campaign’s research has found. Forty percent of Americans are people of color, and people of color are staggeringly over-represented among Americans incarcerated and otherwise impacted by the criminal system—a system whose primary managers, prosecutors, are nearly all white. Put simply, it’s a system of minority rule.

At least part of the justification for the power and discretion we grant prosecutors is the fact that in most states, they are elected, and therefore they are theoretically accountable to the public. In reality, however, prosecutors are a study in unchecked power: We found that in 2018, 80% of elected prosecutors ran unopposed.

We first investigated prosecutors in the aftermath of the notoriously bungled investigation into the killing of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. Robert McCulloch, the white prosecutor who declined to charge Brown’s killer, had been in office for 27 years without facing an opponent at the polls. More recently, Doug Evans, a white DA in Mississippi, has been in the news for trying the same African-American man six times for the same murder, despite every trial ending in a mistrial or having its conviction overturned by a higher court. The case finally made it to the U.S. Supreme Court last year, where the justices ruled that Evans had violated the defendant’s constitutional rights through racially biased jury selection. Yet last November, Evans ran again for re-election, unopposed, and retained the seat he has held since 1991.

The good news is that we can change this broken system. In Missouri, DA McCulloch was defeated in 2018 by Wesley Bell, an African American running on a platform of reform. Across the country, reform-minded prosecutors—led by black women like Kim Foxx in Chicago, Aramis Ayala in Orlando and Rachel Rollins in Boston—have been elected and have begun to make meaningful reforms, though they face tremendous backlash. While in office, they have been held accountable by a growing grassroots movement committed to fundamentally reshaping our criminal system.

Now that movement has come to Georgia, where Ahmaud Arbery’s family is calling for the removal of the two DAs who failed to arrest the McMichaels. Georgia’s Attorney General, under public pressure, has asked the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate the handling of the case; and it has been reassigned to a new DA, Joyette Holmes. Holmes is among the mere 2% of elected prosecutors nationwide who are black women.

Six years ago, the outrage in Ferguson bolstered the criminal-justice reform movement. Today, the fight to achieve justice for Ahmaud Arbery is propelling that movement further. A criminal system managed by elected prosecutors who are 95% white is not just broken; it poses a danger to public safety. The Arbery case demonstrates once again that electing leaders who reflect their communities truly matters—and it reminds us that undoing the racist logic of the criminal system is truly a matter of life and death.

Brenda Choresi Carter is the director of the Reflective Democracy Campaign.