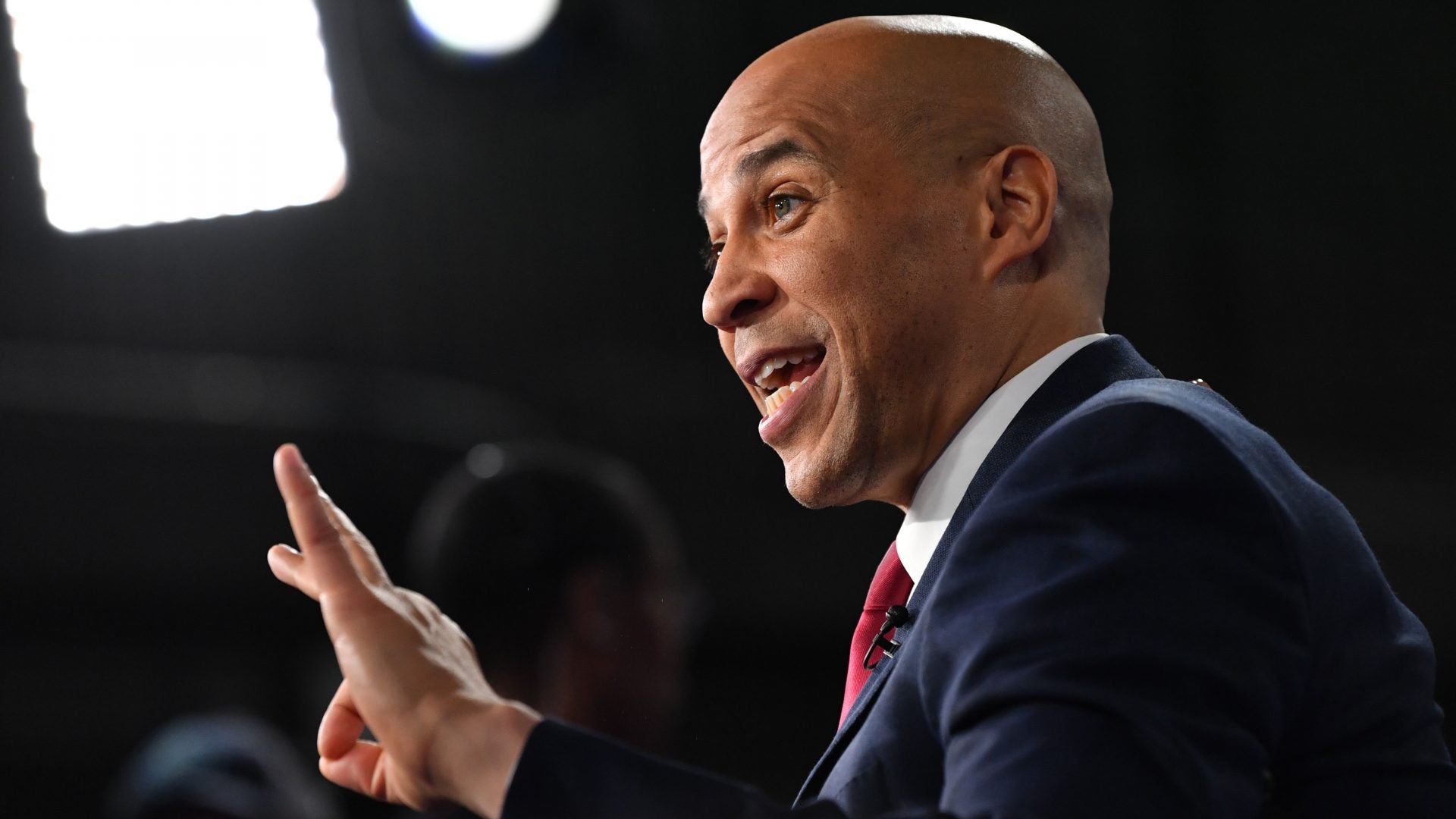

When he launched his presidential bid last year, Cory Booker shared a vision for the country that called on its citizens to “channel our common pain back into our common purpose.”

As he saw it: “The history of our nation is defined by collective action; by interwoven destinies of slaves and abolitionists; of those born here and those who chose America as home; of those who took up arms to defend our country, and those who linked arms to challenge and change it.” It sounded exactly like the Booker we’ve long been familiar with: the upbeat, ultra-positive, genteel politician who believes in the power of love so much that he themed his entire presidential campaign around it.

To his credit, Booker never denied the existing fury of the Democratic base in the era of President Trump.

“I was raised by parents who did not flinch in telling me about the wretchedness of life, about the bigotry, and hate, and violence,” he said in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. “But they taught me that you don’t combat that by abandoning your virtues, but by doubling down on them, and that that is in fact a harder way. … It takes a toughness and a strength. But ultimately it’s the best way to heal, to empower, to strengthen, to overcome.”

Even with the suspension of his campaign, Booker continues to sing about the power of love like Luther (skinny of big Luther, based on your preference).

“Nearly one year ago, I got in the race for president because I believed to my core that the answer to the common pain Americans are feeling right now, the answer to Donald Trump’s hatred and division, is to reignite our spirit of common purpose to take on our biggest challenges and build a more just and fair country for everyone,” Booker wrote in an email to supporters. “I’ve always believed that. I still believe that. I’m proud I never compromised my faith in these principles during this campaign to score political points or tear down others.”

In contrast, Donald Trump mocked Booker.

In 2002, a now-defunct magazine named Shout NY put a then relatively unknown New Jersey politician on its cover, under the headline: “Will Cory Booker Be the First Black President of the United States?”

Of course, Barack Obama’s historic political ascension began two years later, and while a lot of emphases has been placed on recreating the “Obama coalition,” many in media and politics continue to forget that Obama wasn’t just offering a vision of the country that recalls Sesame Street.

Obama’s first presidential campaign was more progressive in terms of policy and tone than it ended up being after he was elected twice (too many anyway). And it came at a time in which then-President George W. Bush brought us to the brink of another depression on top of a litany of other sins from that abysmal period, which brought anti-war protests and the beginnings of the outcries of economic inequality now a major theme of the 2020 election. Obama did lure in the masses with his 2004 DNC speech, but it was the promise of fundamental change that led him to eventually make history.

Unfortunately for Booker, whose past ties to corporate-interests and its impact has long been a source of criticism, while he did offer progressive shifts with respect to gun control and criminal justice reform, on everything else, when asked about issues like a wealth tax, he sounded like a killjoy (albeit some agreed with his larger point), and more than anything, someone who offered nice platitudes but not a coherent enough vision for the change people are really looking for.

Yes, Pete Buttigieg is beloved in spite of his lack of experience, youth, and noted shape-shifting in terms of political stances largely because he is selling the idea of making us one big happy family again sort of like Joe Biden only not as old, but he’s white. That is a double standard, but it speaks to the truth about the electorate. The same can be said of the hope and change espousing Black guy being elected president and succeeded by a bigot.

Booker seems like a genuinely nice person, but the idea of this racist country coming together after electing Trump president was always laughable. The end of campaigns of this magnitude call for moments of reflection, and in this instance, although Cory Booker isn’t in a corner reflecting on his misguided messaging to the score of Faith Evans’ and Mary J. Blige’s rendition of “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore,” other politicians should.

People are angry. People are afraid. People want to fight. Booker may not have wanted voters to continue seeping in those feelings, but it’s hard not to in the Trump era. Whoever is to defeat them has to understand and campaign accordingly.