Grief leaves those who loved deeply drowning, gasping for breath, grasping for anything, anything, that makes sense in and of a world they no longer recognize. It makes it hard to even recognize yourself, the person you once were before the earth opened beneath your feet, yawning miles of nothingness stretched ahead.

Perhaps, that is why 18-year-old Brandt Jean asked Judge Tammy Kemp if he could give Amber Guyger—the racist white (now former) police officer who murdered his brother Botham Jean, 26, just over one year ago—a hug during her sentencing hearing Wednesday afternoon. After finding Guyger guilty of murder Tuesday morning, a Dallas County jury sentenced her to 10 years in prison for her violent crime; she will be eligible for parole in five.

“I love you just like anyone else and I’m not going to hope you rot and die like my brother did,” Brandt Jean told Guyger in a soft, but steady voice.

“I personally want the best for you,” he continued. “I wasn’t going to say this in front of my family, I don’t even want you to go to jail. I want the best for you because I know that’s exactly what Botham would want for you. Give your life to Christ. I think giving your life to Christ is the best thing Botham would want for you,” he said before getting permission from Kemp to give Guyger a hug.

Using his Christian faith as an anchor for his capsized soul, searching for his brother’s guidance amidst the chaos, Brandt Jean, perhaps, leaned the weight of his pain against the only thing in his world left standing, his beliefs. Botham’s beliefs.

I do not know Brandt Jean’s personal walk with grief, as I neither believe in his God, nor share his faith. But I know that haunted look in his eyes; I recognized the confusion, the hurt, the ache. And I witnessed Guyger stride in the fullness of her white woman victimhood and take full advantage of it all. She took control of the embrace—extending it, deepening it, repeating it—until she’d taken all that she could take from him. Then she returned to her seat, comforted by the broken young man left in her wake.

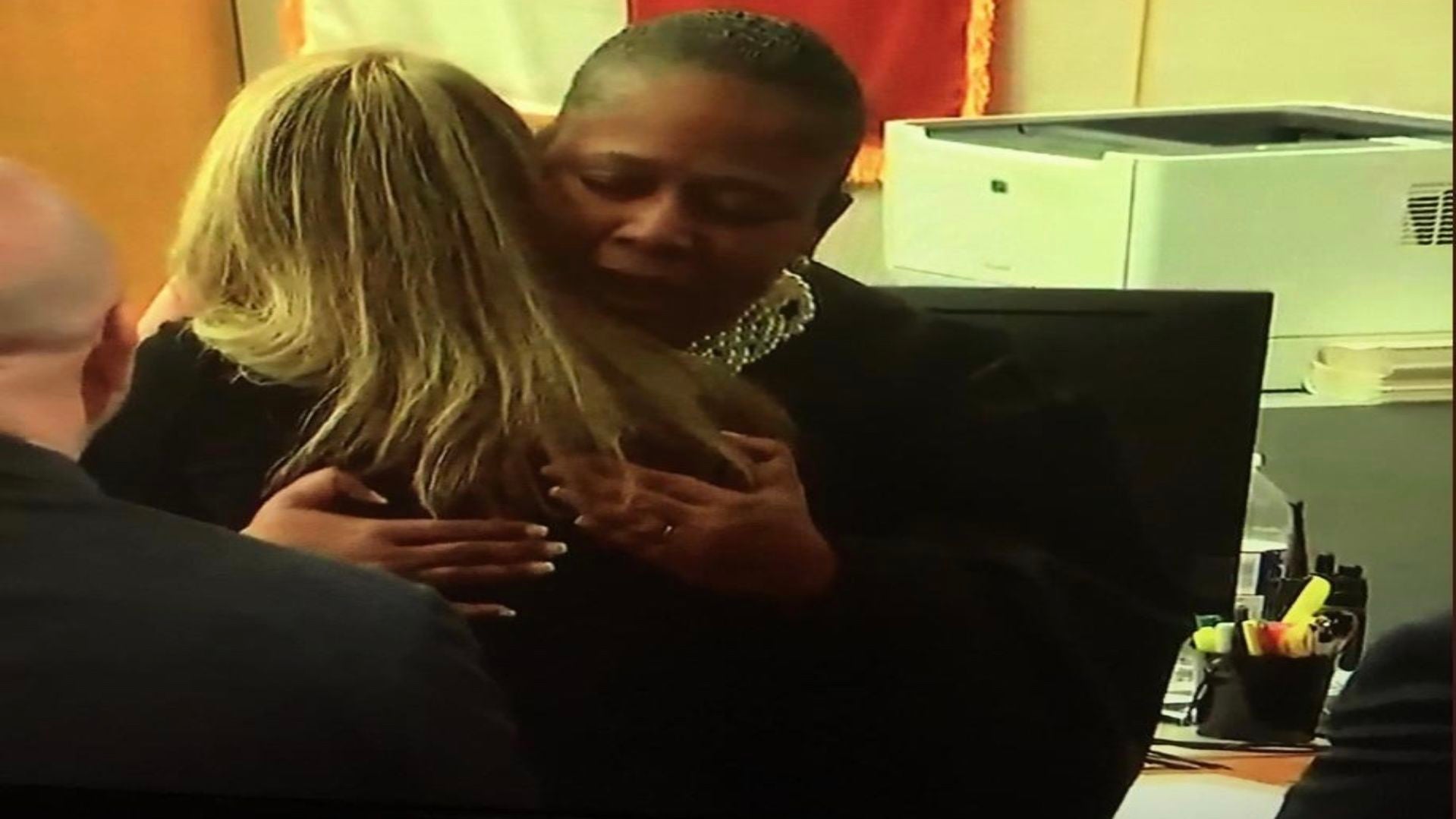

A few moments later, something truly extraordinary happened. Judge Tammy Kemp, the Black woman who presided over Guyger’s murder trial and sentencing hearing, stepped down from the bench and embraced Guyger, too. The judge also handed the convicted murderer her bible and offered her words of support.

“You can have mine,” the judge said to Guyger, of the small bible. “I have three or four at home.”

WFAA reports that Kemp told her, “This is your job,” and then mentioned John 3:16.

“You just need a tiny mustard seed of faith,” the judge said. “You start with this.”

The Court seemed to be in mourning, but not over Botham Jean’s murder. Kemp, instead, seemed to regret that the circumstances surrounding it were so preventable. She seemed to hate that Guyger’s actions were so egregious that it forced this poor, white woman into cage. This time, the law just couldn’t be ignored; it couldn’t be bent or broadened enough for Guyger to slither free. And, that, if the widespread tears of awe in response to both Brandt Jean’s and Kemp’s actions are any indication, was what many people felt was the real tragedy.

During the same sentencing hearing, a Black woman bailiff briefly stroked Guyger’s blonde hair, smoothing as one would a Barbie doll. This is a woman who committed a home invasion, allegedly by mistake, and murdered a man because she perceived him as a dangerous threat to her in his home. A white woman navigating space and time oblivious to those around her and unconcerned with the consequences. A white cop who admitted on the stand to intentionally killing Jean, even though there were multiple other options available to her. As lead prosecutor Jason Hermus pointed out, Guyger chose to leave her key in the door and enter Jean’s apartment. She chose deadly force.

She chose murder.

Yet, this is who Kemp and the unidentified bailiff chose to coddle and cry over. Where were the tears for Botham Jean? Since they clearly rejected any semblance of professionalism and impartiality, where were the tears for his Black mother and his Black grandmother? Or were they not deserving?

Later, in a statement tweeted by the Dallas Police Department, Chief U. Renee Hall claimed that, “Botham Jean’s brother’s request to hug Amber Guyger and Judge Kemp’s gift of her bible to Amber represent a spirit of forgiveness, faith and trust. In this same spirit, we want to move forward in a positive direction with the community.”

Propping up Brandt Jean to serve as a warning and silencer is not “positive.” Hiding within the bruised folds of his humanity is not “positive.” And all three of these agents of the state should be ashamed of themselves. It goes without saying that had a Black police officer committed this same violent felony, leaving Guyger’s body lifeless on the floor, her blonde hair splayed behind her, there would have been no hair strokes and hugs. But there are some Black people who run to shield white people from pain, to protect them from their own actions, to forgive them for their transgressions, as if it gives them—all of them—a first-class ticket to heaven.

No human being deserves to be in a cage, but this notion that Black women must play mammy and Moses for the world is killing us, while police officers with licenses to kill are murdering our children. There is a huge difference between an abolitionist and being openly sympathetic toward a racist killer who didn’t even care enough to administer CPR to Jean as he lay dying. There was no need to remind Guyger—an admitted racist who joked about the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., spraying a crowd gathered to honor him with pepper spray, and the work ethic of Black officers—that “she is kind, she is smart, and she is important.”

Yet, here we are, again, watching people who look like us mortgage their humanity to save white people from their responsibility, their duty, to look in the mirror and reckon with what they see. It should be clear that after generations of white supremacist, anti-Black, state-sanctioned violence, that if those invested in whiteness won’t even look honestly at themselves, they will never see us.

But here we are. Again.

I hope that Botham Jean’s family knows that there are entire communities that wish they could wipe their tears and take away the reason that those tears are necessary. I hope they know we want wholeness and peace and love for them. And as Brandt Jean’s grief continues to shape-shift, ebb and flow, may he grow to understand that rage—whether he has felt it, feels it now, or will feel it again—is righteous, too.

Because, while there may be many people who claim to have seen God in that Dallas, Texas, courtroom Wednesday afternoon, there are many others who still saw a devil.