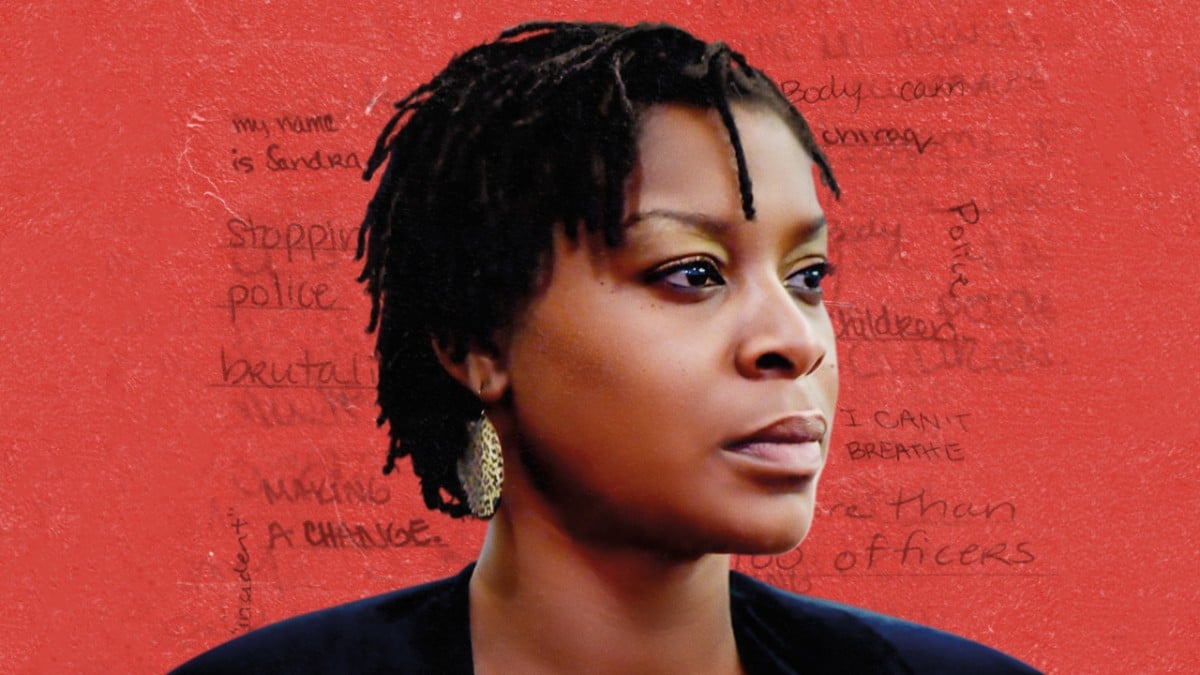

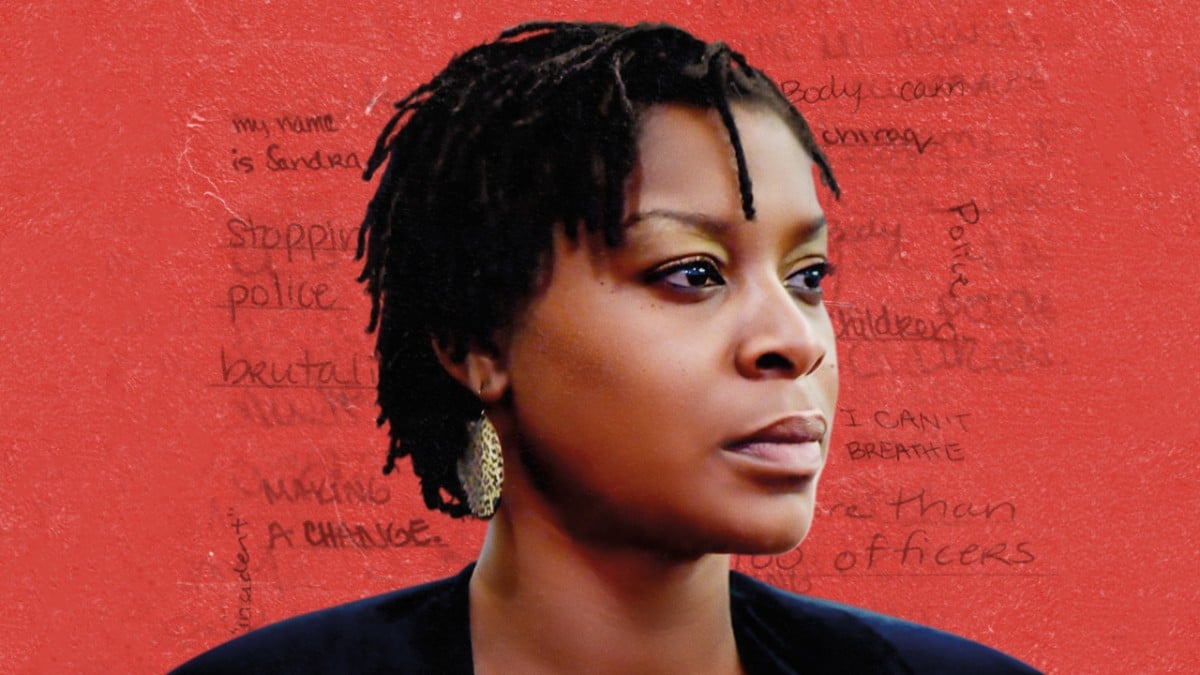

Sandra Bland. Her name, her story, and her 2015 death in a Texas jail cell catapulted one Black woman’s experience of racial profiling, police violence, bail, and jailhouse neglect into the national consciousness.

On Monday night, HBO aired the feature-length documentary Say Her Name: The Life and Death of Sandra Bland. The film is both a heartbreaking journey through Sandra’s final days and a celebration of her life and her family’s struggle for answers and justice. Made in close collaboration with her mother, sisters, and legal team, the story of Sandra’s life is told in their voices, as well as her own, through her #SandySpeaks Facebook posts. The story of her last days, featuring haunting footage of her final moments of freedom, of her face just hours before she was found dead, of her body, the noose authorities claim she used to hang herself, and her autopsy, is told largely through the voices of the people responsible for her death, and leaves viewers with serious questions about what happened in that Texas jail cell.

What is certain is that Bland would still be alive today if she had not been pulled over for a minor traffic offense that every driver commits at some point. If Officer Encinia had simply issued her a warning instead of violently escalating the encounter. If he had not claimed she assaulted him and charged her with a felony. If the judge had not set a $5000 bail (which came out to $500 being needed to make bail) and refused to reconsider her decision. If jail officials had not held Bland in unmonitored isolation for days.

While Bland’s experience is as unique as her beautiful soul, it is also as common as water.

Bland is one of hundreds of Black women who have been killed or died in custody, and thousands who have been violated, abused, threatened, unfairly profiled and targeted by police. The reason her story resonated so deeply and broadly is because it is so familiar to Black women who experience profiling and criminalization on a daily basis, whose compliance with the behavior expected of “Mammy” has been demanded since slavery, at the price of punishment. As I wrote in Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color,

In many ways, Bland came to stand for every Black woman who has ever changed lanes without using a turn signal, expressed frustration at getting a traffic ticket, or experienced depression—so much so that the hashtag #IfIdieinpolicecustody, under which Black women of all backgrounds expressed their fears of, and resistance to, sharing Bland’s fate, trended on social media.

When I first heard her story, it reminded me of another traffic stop, of another young Black woman named Sandra, across the country, almost 20 years earlier. In 1996 a white officer pulled Sandra Antor over as she drove home to visit friends in North Carolina, violently dragged her out of her car, and threatened to make her “taste liquid hell” with pepper spray, much like Officer Encinia threatened to light Bland up with a TASER. He then threw her down on the side of the highway, straddled her and hit her in ways similar to cellphone camera footage of Bland’s violent arrest by Officer Encinia.

But what is truly striking is that Sandra Antor’s explanation of what she thought the officer was thinking as he was hitting her: “Damn Black bitch.” “He was pissed … Who the hell do I think I am? Don’t I know where I am? This is his neck of the woods,” adopting a white Southern accent for the last sentence, could just as easily describe Bland’s arrest, and countless other daily interactions between Black women and police that didn’t make national news in the two decades between the two incidents.

The numbers show Black women are routinely targeted for Driving While Black. In fact, in Ferguson, MO., the year before Mike Brown was killed, Black women were the group most likely to be pulled over by police, more so than Black men. In Sandra’s hometown of Chicago, over 60% of young Black women reported experiencing a car or pedestrian stop in 2015, and more young Black women reported being pulled over by police when driving than young Black men.

Black women also routinely experience police violence – in fact, a recent study found that Black women are the group most likely to be killed by police when unarmed.

Black women are also the fastest growing prison and jail populations, often held on minor offenses, often because they are unable to post bail – with sometimes deadly consequences. As Sandra’s mother, Geneva Reed-Veal, a central figure of the film, points out, 5 other Black women died in jails the same month as Sandra. More have since, including Deborah Lyons, a 51 year-old Black mother found hanging in the Harris County jail this past July, 5 years after and just a few hundred miles from where Sandra died in the Waller County jail.

Context is critical to ensuring that Bland’s story is not seen as an exception to the rule that men are the primary subjects of racial profiling and police violence, making her all too often the only woman mentioned on long lists of Black men targeted by police, but rather as a reflection of broader patterns of policing. Until we start understanding stories like Sandra’s not as isolated tragic incidents, but as an integral part of the systemic racism in America she herself decried, Black women will continue to be violated and killed by police with impunity.

Hopefully the film will serve as a clarion call to a broader conversation – and to action. As Geneva Reed-Veal, whose continuing activism and efforts to pass the Sandra Bland Act in Texas are described in the film, testified before Congress in 2016: “We have got to stop talking and move. So I leave you with this: it is time to wake up, get up, step up or shut up.”

That is exactly what the #SayHerName organizing efforts the film takes its name from, but barely touches on, are all about: from the Say Her Name: Resisting Police Violence Against Black Women report first published by the African American Policy Forum in May of 2015, gathering the stories of dozens of Black women, some, like LaTanya Haggerty, also killed after traffic stops by police, and several, like Mya Hall and Korryn Gaines, also killed in 2015; to the movement launched under the #SayHerName hashtag for another Chicago daughter, Rekia Boyd, whose 2012 killing also followed a perceived failure to comply with the orders of a way off-base white police officer; to more mothers’ and sisters’ efforts to secure justice for their loved ones Michelle Cusseaux, Tanisha Anderson, and Kayla Moore; to the many ways #SayHerName has served as rallying cry for so many Black women who have been targeted for police violence, criminalization, and incarceration. There is so much more to the larger #BlackLivesMatter movement Sandra was inspired by – and which eventually mobilized in her name – that viewers outraged by the film can plug into than is depicted in the film’s sensationalistic and distorted footage of a tense standoff between armed New Black Panthers and police outside the jail where Sandra died, and the brief collage of clips from what were actually national days of action featuring vigils and demonstrations in Sandra’s honor across the country held two years in a row on the anniversary of her death.

If we want to see the action Bland’s family is calling for, we need to do more than say Bland’s name and tell her story in isolation. We need to honor Bland’s memory by lifting up and supporting movements working to undo the conditions that contributed to her death, including organizing efforts to end racial profiling of Black women on streets, at borders, in homes, at schools, and in hospitals, to bail out Black women and end pretrial detention on money bail, to end solitary confinement, and to challenge incarceration, denial of medical care and neglect of people with disabilities.

These organizing efforts are our tribute to Bland and our answer to her family’s calls for justice and accountability. This is the work we do in Bland’s name, in Bland’s honor, to challenge the ways policing shaped her life, to eliminate the conditions that contributed to her death, and to stop what happened to her from happening to one more Black woman.

This is what it means to Say Her Name.

Andrea J. Ritchie is the co-author of

Say Her Name: Resisting Police Violence Against Black Women, published by the African American Policy Forum, and the author of

Invisible No More: Police Violence Against Black Women and Women of Color. She has been organizing, advocating, litigating and agitating around profiling, policing and criminalization of Black women, girls, trans and gender nonconforming people for over two decades.